The recent passing of Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, the last living major player of the Latin American Boom, along with Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes, certifies that this 20th century phenomenon is truly over. A new chapter is being written today by younger novelists, as well as those scholars, editors and translators whose backward glance instructs us, and without whom the Boom, a truly international phenomenon, could not have transcended beyond Spanish.

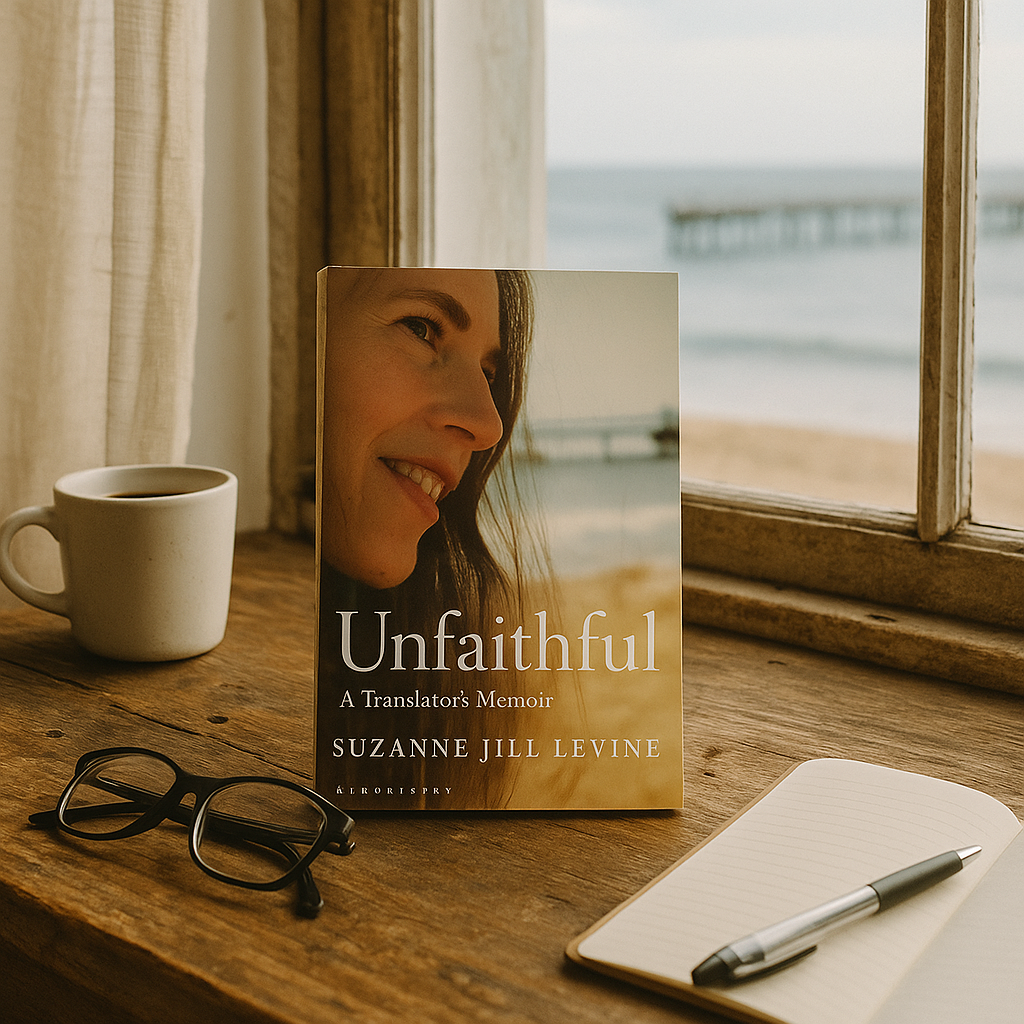

Scholar and translator Suzanne Jill Levine is one of those key players whose moving memoir takes account of her decades-long personal stake in that narrative. Unfaithful: A Translator’s Memoir (New York: Bloomsbury, 2025), the third and most intimate installment of a trio of essays that includes her Subversive Scribe: Translating Latin American Fiction (1991) and the biography Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman (2001), tells the story of insertion in the Boom during her twenties, crafting seemingly untranslatable works during her thirties and forties, while reflecting upon the craft in her later years. But because this time her story accounts as well for her relationships with the people involved, including mentors and writers, and her own psycho-sexual evolution, Unfaithful takes the reader behind the scenes of cultural production to reveal the mutual transformation, Levine’s own embodied translation, of work and agent from marginal to essential player.

In five chapters and four shorter, less central essays, the book describes working contact, and at times intimate collaboration, with people like Emir Rodríguez Monegal, the scholar and editor who is credited with initiating rhe Boom during the sixties and whom Levine met in New York when she was still a student; or else, often through Monegal’s good graces, with writers like Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Manuel Puig, or Adolfo Bioy Casares, whose works in time she would translate. Neither a history nor a series of readings, the book provides a personal chronicle of what it was like for a young American Jewish woman to live and work among writers whose talent at the time thrust them, and her, onto the world stage. Her impressions, told in pellucid recollection, are always entertaining, often trenchant, and at times confessional, as when she describes her years-long relationship, awkward but ultimately satisfying, with Monegal, who was twenty-five years her senior, or her slow discovery of her attraction to women. Thus, after describing her early acquisition of Spanish and haphazard acquaintance with the relevant publishing worlds, each chapter frames the episodes of her personal evolution with the projects she tackled at the time. Among these challenges figure prominently tours de force like Three Trapped Tigers, Cabrera Infante’s Joycean recreation of Cuban jargons during pre-revolutionary days, or the mannered Argentine inflexions, filtered through Hollywood melodramas, in Manuel Puig’s Betrayed by Rita Hayworth. Masterpieces of translation like those two, among very many others Levine produced over the years, earned her a reputation as a skillful and creative crafter who went as far as collaborating closely (Cabrera Infante coined it as closelaboration) with the writers themselves and helped raise translation to a veritable artform.

And yet, without ever intending to wax theoretical, Levine’s life story suggests questions seldom if ever posed in similar essays. Orphaned while still in college, the story juxtaposes personal loss and foreign language acquisition, an exchange that anchors linguistic awareness upon internal turmoil. In her chapter on Monegal, Levine in fact credits his own parental loss as part a strong component of their common emotional link. What is, then, the conceptual link between translation and loss, or else between language and death? The theme and fact of loss does figure prominently in this chronicle of both textual translation and personal transformation, to which one can attach the, perhaps stretched, trove that writers like Cabrera Infante and Puig were, at the time Levine worked with them, de facto exiles whose works jointly dramatize a search for anchors in a stateless idiom—one through sex and popular music, the other through the specters of radio and of film. Add to all this the fact that virtually the entire “cast of characters” —all of them acquaintances, some close friends, a few lovers–in Levine’s Unfaithful, from Borges and Bioy Casares to Arenas and Sarduy, are all dead. Hers is a paean that turns memoir into memorial, a moving exercise in prosopopeia, the rhetorical figure for the address to the dead, that cannot be dismissed simply as a curious footnote from a marginal player.

The impact that Boom writers and their works have had on several generations of readers—from the education of literary taste to the awareness of history and politics—is a reality that Unfaithful complements in essential ways. For the Boom marked the apotheosis of literary language, and its translation was one of the ways in which that triumph was globally achieved.

How can I see the posted comments on this review?