Flâneur of words, Roland Barthes strolled through the tangible streets of the invisible (literature), knowing that each step was supported by a pile of stumbles. Barthes did not think of irony as a parlor trick or a hat that is removed to greet the reader with sarcasm; he thought of it as a crack that opens on the loving side of discourse, to let an insistent question escape: “What if language said nothing more than its own doubt?”

In the 1960s, with the world engulfed in heated theoretical debates, Barthes encountered Raymond Picard, that gatekeeper of “scientific” criticism, armed with dictionaries and more or less comfortable certainties. Picard wanted to measure literature with the rule of the literal, as if a verse by Racine about Nero were just a weather report or a belated horoscope. Instead, Barthes responded with a restrained laugh, an irony that plays with forms without touching beings, that never attacks head-on. “I wish that had been said ironically,” he said in the pages of Criticism and Truth, and with that simple phrase he disarmed his opponent’s arsenal. For is irony not the critic’s last refuge when science seeks to strip language down to its bare bones? The author of Mythologies pointed out that distance that does not hurt entirely, that allows us to look up and see what science overlooks: the game, the plural, the “second language” where everything is open to possibility, but which escapes all fixity.

Years later, Barthes delved into the labyrinth of a story by Balzac, Sarrasine, and took it apart in S/Z to see if time is inside or only in the gears. There, irony becomes the very pulse of the life being narrated: nothing explains the world to us except what others have written about it, and in that web of texts we become entangled in a spider’s web of borrowed meaning. The “beautiful” prose that speaks of the meaninglessness of existence becomes ironic by pure contrast, because while it describes emptiness, it itself fills it with beauty, and the reader—poor deluded soul—passes through it without noticing that he has just fallen into the trap. Symbols—with their subjective magic—ironize our moralizing, inviting an openness that dissolves all prescription, all Truth. Barthes extended this to the entire novel, quoting Lukács or Goldman. Irony thus becomes the way in which the novelist rises above his characters, with their limited consciousness, and exposes the cracks in society; fissures that might lead the reader to wonder if they are not, in the end, his own. In Balzac, realism pretends to capture life “as it is,” but by ordering it into chapters and dialogues, it reveals its absurdity: a structure that promises Truth but delivers a blurred mirror.

And then comes the intimate, that twist where Barthes becomes almost confessional, as if irony, after so much wandering through the halls of criticism, had slipped into the bedroom of the cœur. In Fragments of a Lover’s Discourse, the “I” in love presents itself as a smiling solipsism, tying “I love you” into an absurd knot of words that bind nothing solid. “It is really a matter of agglutination,” he says with that smile, the same one that recognizes that love is discourse only for oneself, grandiloquent and pathetic in equal measure, an adjective that describes waiting without promising an embrace. It is as if Barthes were telling us a bedroom anecdote: the lover who loses himself in his own metaphors, quietly mocking his own fever, because he knows that the other, the beloved, is always a horizon that gracefully recedes.

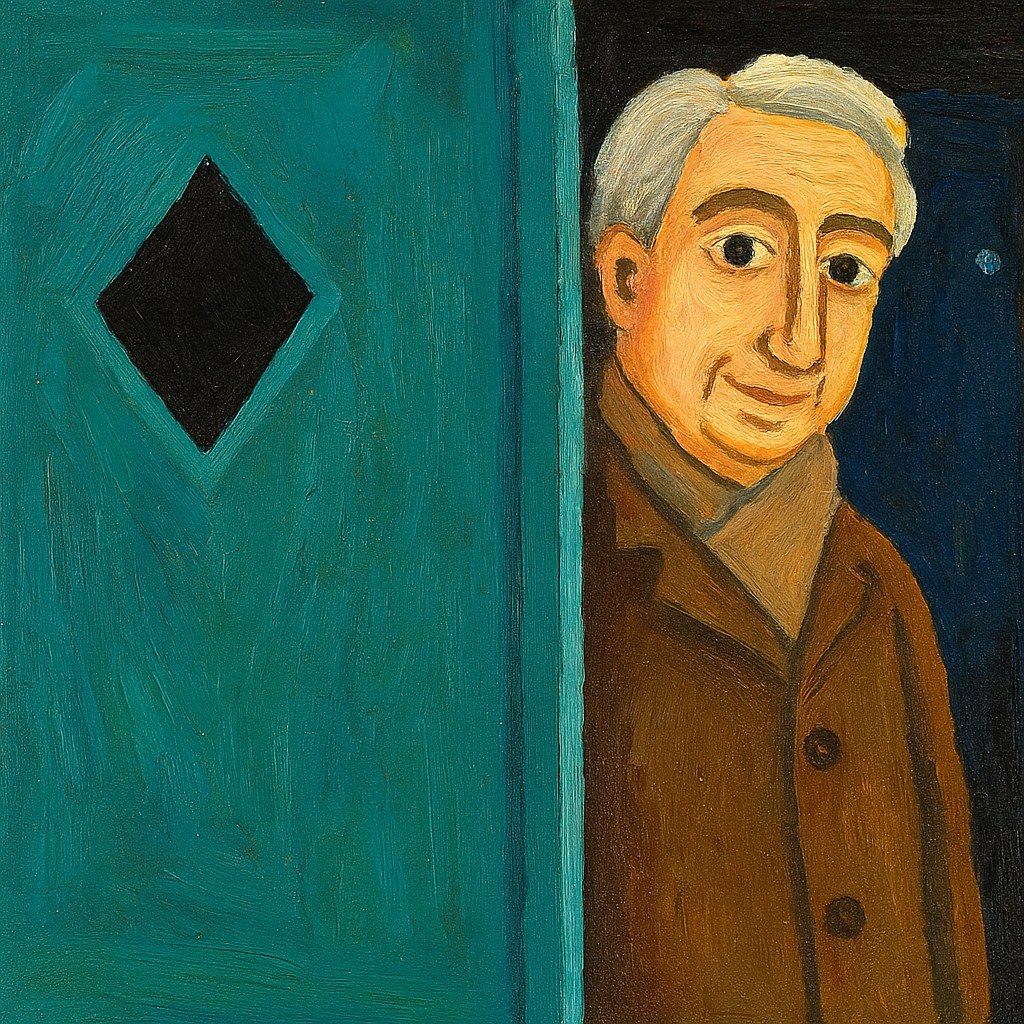

Even in his own life, woven from fragments like an improvised collage, irony appears with a prudence that borders on coquetry. He did not like 1915, the year he was born: “a bland year, lost in war, without famous events or births.” But underlying that humble complaint is a subtle glory, that of someone who hides in order to show himself better. In Sade, Fourier, Loyola, he fantasizes about minimal biographies, made up of “details, preferences, inflections,” as if his own existence were not already an autofiction revolving around an empty subject, an ironic echo of feigned sincerity. For Coetzee, that other maker of oblique truths, all “autobiography is never a faithful portrait, but a dance with the shadow,” where “romantic irony makes doubt the only possible portrait.”

Barthes and his irony are an alliance against the certainties of a single path, a dance on the neutral ground of “neither this nor that,” which explores the undecidable. Today, inundated with discourses that bombard us with prefabricated truths, rereading it with a touch of irony is like turning on a flashlight in the fog: language, that old joker, has always preceded us, chuckling quietly at our pretensions of control. Barthesian baroque irony—the kind that “opens up language”—calls us to its playful abysses, where every question is an invitation to keep walking.