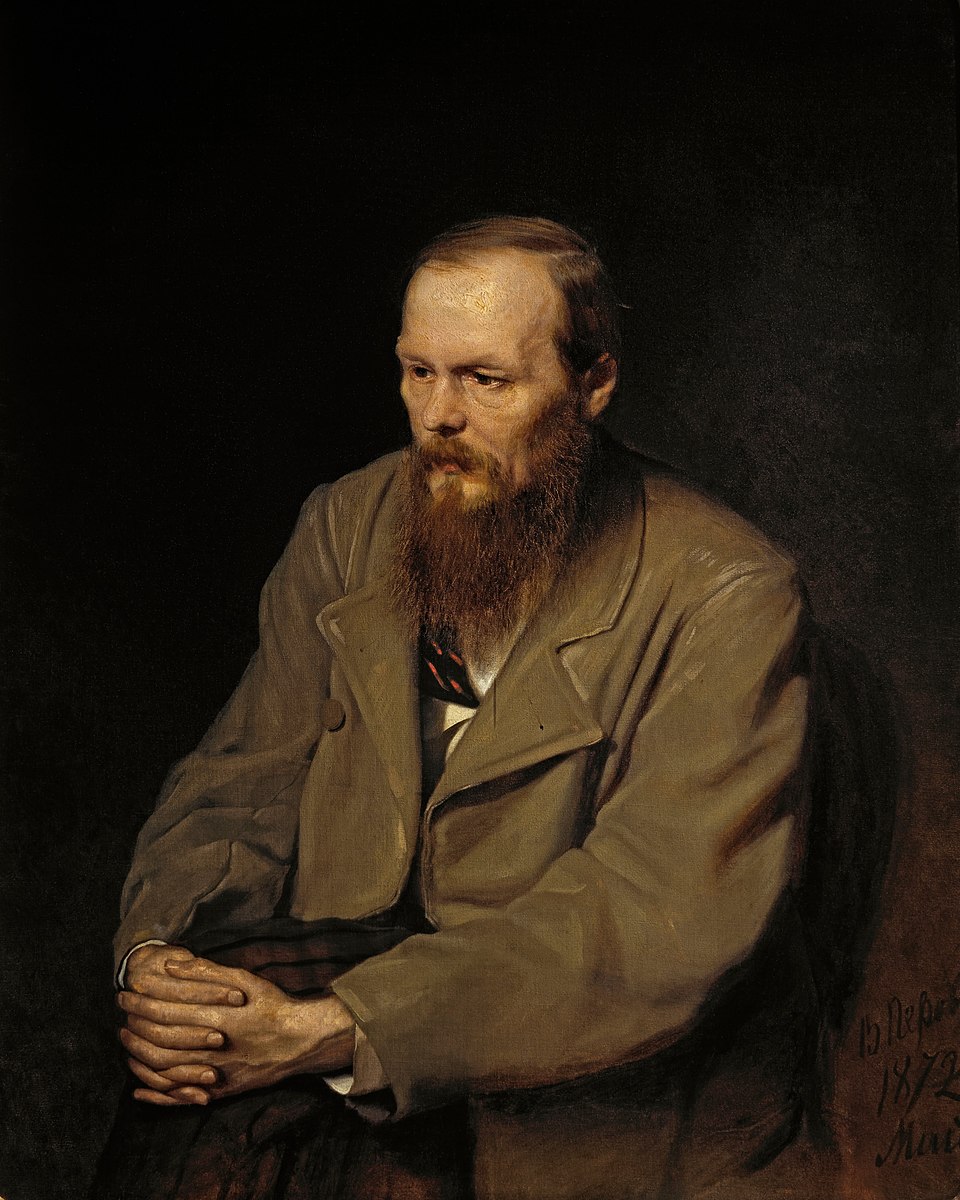

Citario. Derived from the Latin “citāre” (to quote) plus the suffix “-ārium” (repository), similar to “bestiary.” A 21st-century neologism, it emerged among Spanish-speaking scholars at Bookish & Co., with roots in ancient anthologies and florilegia. “Citario” is related to medieval books of commonplaces (such as Erasmus’s) and 19th-century proto-examples, such as “Familiar Quotations.” This “Citario Dostoevsky” celebrates the 204th birthday of the writer who reinvented the modern novel from a ‘sustained crisis, a state of metaphysical emergency,’ in the words of George Steiner.

Dostoevsky is the creator of the polyphonic novel. He managed to form a fundamentally new novelistic genre. That is why his work does not fit into any framework; it is not subject to any of the historical-literary schemes that we are accustomed to applying to the phenomena of the European novel. In his works, a hero appears whose voice is formed in the same way as the author’s voice is constituted in a common type of novel. The hero’s discourse about the world and about himself is as autonomous as a normal authorial discourse; the hero’s word is not subordinated to the objectual image of its bearer as one of its characteristics, nor is it the author’s spokesperson. It has an exceptional independence in the structure of the work; it seems to sound alongside the author’s word and relates in a special way to it and to the equally autonomous voices of other heroes.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1963)

◾️

Russian authors before the war do not know how to give contour to existence. They cannot—excluding Tolstoy—trace a destiny. Everything is presented to them from the inner side of experience. However, they have discovered the dynamic of events for the novel, that space of tension closed off on all sides. Thus, the Russian novel of the second half of the last century, with Dostoevsky as its most valid representative, created a new type of reader. This should be understood as follows: when I close a novel by Stendhal or Flaubert, a novel by Dickens or Keller, I feel as if I am stepping out of a house into the open air. No matter how deeply I immersed myself in the narrative, I always remain myself, feeling determined in many diverse ways and with different intensities, but always within the proportions of the space I occupy, that is, without my substance being transformed and without losing control of consciousness. In contrast, when I finish a book by Dostoevsky, I first have to return to myself, reestablish myself. I must orient myself, as upon waking, after having perceived myself vaguely during the reading, as during a dream. For Dostoevsky delivers my consciousness bound hand and foot to the horrifying laboratory of his fantasy, exposing it to events, visions, and voices that are alien to me and in which it dissolves. Even the most trivial of his characters is abandoned to their fate, delivered to it with their hands tied. This procedure, in itself not without problems, is certified by the dimension of the attempt that the author makes in the realm of religious and moral experience.

Walter Benjamin, “Reading Dostoevsky” (La tarea del crítico, Editorial Hueders, Santiago de Chile, 2017)

◾️

Like the discovery of love, like the discovery of the sea, the discovery of Dostoevsky marks a memorable date in our lives. It usually corresponds to adolescence; maturity seeks and discovers serene writers. In 1915, in Geneva, I avidly read

Crime and Punishment in the very readable English version by Constance Garnett. That novel, whose heroes are a murderer and a harlot, seemed no less terrible to me than the war that surrounded us. I looked for a biography of the author. The son of a military surgeon who was murdered, Dostoevsky (1821-1881) experienced poverty, illness, prison, exile, the assiduous practice of letters, travel, a passion for gambling and, at the end of his days, fame. He professed the cult of Balzac. Involved in a vague conspiracy, he was condemned to death. Almost at the foot of the gallows, where his companions had been executed, the sentence was commuted, but Dostoevsky served four years of forced labor in Siberia, which he would never forget.

He studied and expounded the utopias of Fourier, Owen, and Saint-Simon. He was a socialist and a pan-Slavist. I had imagined that Dostoevsky was a kind of great, unfathomable God, capable of understanding and justifying all beings. I was astonished that he had ever stooped to mere politics, which discriminates and condemns.

To read a book by Dostoevsky is to enter a great city that we don’t know, or the shadow of a battle. Crime and Punishment had revealed to me, among other things, a world foreign to me. I began reading Demons and something very strange happened. I felt that I had returned to my homeland. The steppe in the work was a magnification of the Pampa. Varvara Petrovna and Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky were, despite their uncomfortable names, old irresponsible Argentines. The book begins with joy, as if the narrator did not know the tragic end.

In the preface to an anthology of Russian literature, Vladimir Nabokov declared that he had not found a single page of Dostoevsky worthy of being included. This means that Dostoevsky should not be judged by each page but by the sum of the pages that make up the book.

Jorge Luis Borges, Miscellaneous Works

◾️

The “Unique One” was in young Dostoevsky’s library. And the book also circulated among the Petrashevsky circle, that perversely candid group of subversives who would be dissolved before the rifles pointed by the officers of Nicholas I, before dispersing to the “houses of the dead”. But in the Dostoevsky-Stirner relationship we find something much more serious than a coordination of ideas: the anthropological monstrum presented by Stirner would continue to live on in Dostoevsky’s novels. The ‘Unique One’ introduces a violent reactive into psychology, something that provokes distance from everything offered as Law: in the first place, identity, the system of equivalences, and thus everything else, right down to functions, class conventions, established feelings. With Dostoevsky, such a disordering of everything human, the breath of arbitrariness, a fluctuating disturbance between characters, an impossibility of drawing defined profiles, bursts into the novel. The cloud-shaped psyche evades every crack and envelops the city. That being whom Stirner calls the unique one is, in the first place, an formless cavity: Dostoevsky evokes from that cavity teeming faces, the underground man, who in his just anonymity somehow encompasses them all, but also Raskolnikov, Kirilov, Ivan.

Dostoevsky inhabits the underground in the same way that Zarathustra inhabits his mountain cave, but he will not shelter the “higher men”. Instead, he awaits Stirner’s Unmensch…

Roberto Calasso, The ruin of Kasch (1983)

◾️

Another day, if we are to believe Sonia’s account, he spoke to the young sisters about his first epileptic attack. He had just gotten out of prison and was living confined in Siberia when he received a visit from an old friend. Although it was Easter eve, the joy of meeting made them forget the most important religious holiday of the year. They spent the whole night talking, tireless, without worrying about the time, getting drunk on their own words. Dostoevsky’s friend was an atheist. Dostoevsky was a believer (or rather, he tried with all his will and desperation to be one). “God exists, God exists!”, he shouted at the height of his exaltation. At that very instant, the bells of the neighboring church began to peal, making the opaque air of the night vibrate. “I felt that heaven descended upon the earth and swallowed me up”, Dostoevsky told the silent and attentive girls. “It was as if I found myself in the presence of God; He got into the deepest crevices of my soul. God exists, I shouted once more, and after that I remember nothing else… You, you who are well,” he continued, raising his voice, “do not know what happiness is, that happiness that invades the epileptic an instant before the seizure. I couldn’t say if it lasts a few seconds, hours, or months, but believe me, I wouldn’t trade it for all the joys in the world.” Dostoevsky said these last words lowering his voice, until it returned to a passionate and broken whisper. The two young women were hypnotized and enchanted. He attracted and repelled them, frightened and seduced them, and sowed a painful uneasiness in their hearts.

Pietro Citati, Il male assoluto: nel cuore del romanzo dell’Ottocento (2000)

◾️

What Starobinski said of Rousseau—that he “wrote to live in the text what he could not live in life”—applies revealingly to Dostoevsky. That is why, in the Russian novel, the trivial becomes symbolic, and the grotesque becomes judgment. This ethical combustion is manifested in Rodion Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. More than a simple criminal act, his crime embodies the implementation of a personal philosophical theory, an experiment to determine whether he belongs to the category of “extraordinary men.” His confession to Sonia is that of a theologian of his own pride (…)

Thus, Raskolnikov’s is a metaphysical drama. He is his own moral system in crisis, a “portable theology” that collapses in the face of his soul’s situation. While Tolstoy legislates, Dostoevsky warns; hence, for Steiner, the writing of the author of Memoirs from the Underground is “sustained crisis, a state of metaphysical emergency.”

Pablo de Cuba Soria, “Russia or the Novel as Destiny” (Bookish and Company, july 24, 2025; https://www.bookishandcompany.com/en/russia-or-the-novel-as-destiny/

◾️

Nechaev was arrested in Switzerland when Dostoevsky’s novel [Demons] came to light, and during his decade as a prisoner, the terrorist managed to seduce the soldiers guarding him, who were on the verge of facilitating his escape. But on March 13, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by terrorists, and that success deprived Nechaev of his liberation. Dostoevsky had died a month earlier

When the murder of Ivanov occurred in 1869, Dostoevsky had already begun writing Demons, his great novel about nihilism, another settling of scores. With that book, Dostoevsky made explicit his break with the liberalism of his own generation, which, by turning its back on the Russia of the throne and the altar, had engendered the young terrorist generation. Demons was the answer to Fathers and Sons (1862), Turgenev’s novel whose ambiguity allowed it to be used either for or against nihilism, the phenomenon he had baptized. Joseph Frank, after reading the press of the time with his usual thoroughness, states that the Dostoevskian terrorists resemble the radical personalities who inspired them too much to continue asserting that they were merely a caricature.

J. M. Coetzee dedicated a novel (The Master of Petersburg, 1994) to the imaginary relationship between Dostoevsky and Nechaev. In Coetzee’s fiction, Ivanov, the murdered student, would be Dostoevsky’s adopted son, who travels clandestinely to St. Petersburg to investigate his death and ends up running into the demiurge Nechaev, who will try to put him at the service of the cause. Coetzee’s parable brilliantly illustrates what was at stake for Dostoevsky when writing Demons, a political pamphlet transformed into a prophecy about the destiny of Russia and the revolutionary soul during the 20th century.

Christopher Domínguez Michael, “The devil’s children” (El XIX en el XXI, 2010)

◾️

With a genius in whom Christian charity intertwined with the most turbid experience of modern nihilism, Dostoevsky showed how tragic and at the same time ridiculously banal the transgressive seduction is, which invites one to infringe the moral law in the name of the unfathomable and muddy flow of life; his heroes, like Raskolnikov or each one of us, are great in suffering and ultimately in the perversity that leads one to be dazzled by the trash of evil, interpreting to the letter the first books that come within reach, devoured hastily and poorly digested. Perhaps only Dante has succeeded in an equal measure in making his characters speak from within their dramas, without overwhelming them with the decalogue of values in which he firmly believed. Dostoevsky does not impose the Gospel even on his most abject figures, on the voice of their torn depravity; moreover, it is precisely the Gospel that urges him to listen, without censorship, to the most dissonant expressions of the human heart. In that modern Divine Comedy that is his narrative, the Dantesque circles have been transformed into the stairs and dark corridors of the popular neighborhoods of the metropolis, the truest landscape of our poetry, our theater of the world.

Claudio Magris, Journeying (2018)

◾️

Like Balzac, when he was writing novels, the “reactionary” Dostoevsky stopped being one and became someone very different; not exactly a progressive, but a crazed libertarian, someone who explored human intimacy with boundless audacity, digging into the depths of the mind or soul (to somehow designate what only much later Freud would call the subconscious) for the roots of human cruelty and violence. This extraordinary transformation is very clearly seen in Demons. There is no doubt that Sergey Nechaev is the model that Dostoevsky used to build the character of Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky, a more or less stupid ideologue who, in order to save humanity, is first willing to make it disappear with crimes, fires, and various atrocities.

Mario Vargas Llosa, “Nechaev heirs”

Post Views: 12