There is a passage in La jaula de la melancolía by Mexican sociologist and essayist Roger Bartra where he attempts to demystify the national interpretation essays that brought prominence to his country’s literature and thought in the first half of the 20th century, such as Octavio Paz’s classic El laberinto de la soledad. In these essays, he states:

[W]e glimpse…the gestation of a modern myth based on the complex processes of mediation and legitimation that a society unleashes when the revolutionary forces that constituted it decline (Bartra, 87).

Could something similar be found in Cuba, considering that there has also been a tradition of national interpretation in essays during the same period? Are José Antonio Ramos’ Manual del perfecto fulanista, Jorge Mañach’s Indagación del choteo, and Lino Novás Calvo’s El pathos cubano examples of this same phenomenon? The question is relevant, although it seems to be refuted by the fact that Cuba experienced a revolution of independence between 1895 and 1898, but two of the essays mentioned were written during the period when a new revolution was brewing, that of 1933.

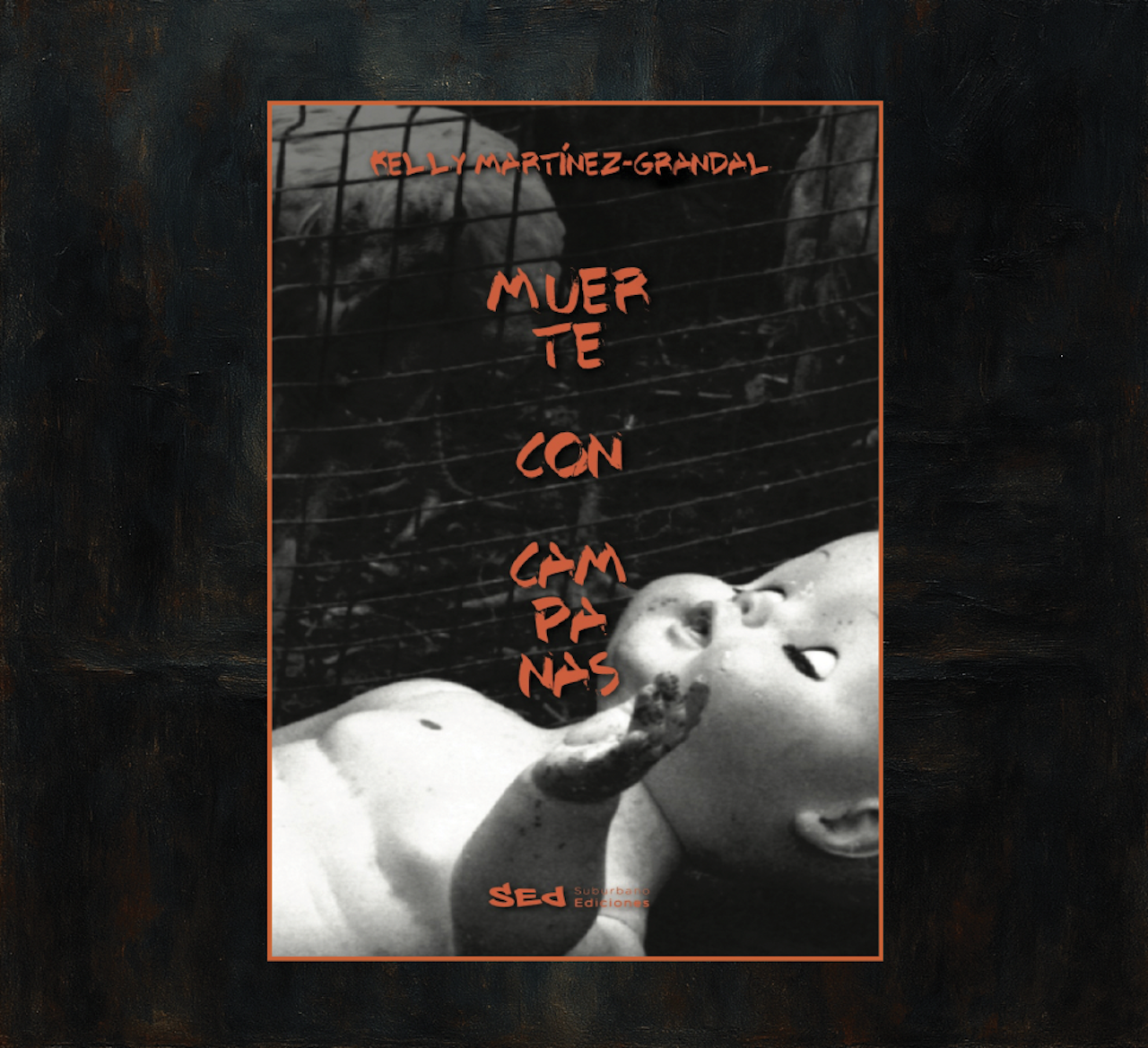

However, at the end of the 20th century, another revolutionary decline occurred, corresponding to that of 1959. Are we witnessing the creation of a myth? That of the post-revolutionary Cuban who is indifferent to beauty and capable of succumbing to stereotypes typical of Western culture, such as the contrast between civilization and barbarism. This is what seems to emerge from reading the stories in Muerte con campanas by Miami-based Cuban writer Kelly Martínez-Grandal.

The book, published in 2021, which I enjoyed reading, caught my attention recently when I began to study the Generación Cero (Generation Zero), to which Martínez-Grandal belongs and which brings together Cuban writers born in the 1970s and early 1980s, marked by the tensions caused by the revolutionary eclipse and the experience of exile and emigration, tensions that could be called characteristic of post-national literature from a certain academic perspective.

The book maintains the unity that a novel might have given the similarities of its characters: emigrants or individuals who want to escape failed revolutionary utopias such as Castroism or Chavism. In one of the stories, one of the most tragically tense despite being grouped together with stories of murder and abandoning everything one owns to achieve freedom, the protagonist decides to attend one of the rituals that define women in Miami: waxing. There she is attended by a young Russian woman whom the protagonist describes as beautiful. However, at one point during the treatment, the heat of the wax causes the client to feel such intense pain that she exclaims: “Be careful, I’m not Russian.”

The narrator explains the reason for this expression, which her interlocutor says she does not understand at first: “I always imagined Russians as a tough race,” she explains. Knowing that the protagonist is Cuban, we can infer the national myth. The Antillean is not a strong race; it has always been easy prey for empires. This seems to confirm the idea of Antonio Benítez Rojo who, entering the field of cultural history, suggests the hypothesis that the greatest resistance of the Caribbean, even the Spanish, to emancipation came from its plantation system. (La isla..,69-74) And Hegel, two centuries earlier, saw weakness in the inhabitants of the Americas.

These national stereotypes immediately clash with others of an opposite nature: “A friend told me that when the Trans-Siberian Railway—the train that connects the capital with the Asian borders of the former Russian empire—passes in front of the birch trees, everyone hugs and cries.” This stereotype, this national myth (Russian sensitivity) is corroborated in the story, as the young Russian woman, Mashenka, is hurt by the reaction of her Cuban client: “I know people like you. They think Russians are insensitive because we come from the cold and communism, that we solve everything with vodka and ice.” Here the stereotypes are reversed, with the Cuban woman coming across as tough and insensitive and the Russian woman as sentimental. Is this insensitivity in the Cuban woman a result of the image that Russia has had under the revolution? The subject would be worthy of a study which, due to its length, I am unable to address here. However, I am inclined to accept this interpretation of the story, bearing in mind that the protagonist replies: “Have your people become insensitive under communism?”

Here, another myth could also appear, in Bartra’s style, about national character. Cubans have suffered under communism, but this is something totally alien to our idiosyncrasy. We are sensitive, sensual (if this is not a contradiction), and we do not identify with the sacrifice of our society for a disastrous ideal or with hatred of imperialism. We have not been just any communist country; they, the Russians, have been one and the same with that philosophical monstrosity. They are the East, we are the West.” And it is a myth that seems to have been reaffirmed in the recent Cuban experience in Miami.

The protagonist attempts an apology that will free her from the image of the ignorant foreigner, an image often applied to Americans, appealing to her knowledge of literature and other branches of Russian culture, widely published in Cuba during the author’s childhood, but she realizes that this knowledge does not exempt her from her prejudices. The story ends by revealing to the protagonist the tragedy of behaving perhaps like her companions who had convinced her to participate in the aesthetic ritual by reproducing the myth about Russia in the Cuban mindset: her readings of Tolstoy and Pushkin had been of no use to her. Unlike the myth pointed out by Bartra for Mexico, that of post-revolutionary Cuba does not seem to have been created by intellectuals but by the people, although reading a letter from Gastón Baquero to Lydia Cabrera reaffirms this. [1]

The exiled writer Roberto Luque Escalona once called Cuba “the country of myths.” Rereading this summer a forgotten book by Luis Aguilar León, a journalist who could be included in the tradition of national interpretive essayists, I found a passage in which he constructed a satirical dialogue between a grandfather who returns with his grandson as a tourist to the United States of the future, when Cuba has become a completely post-communist nation: “When we arrived here,” says the grandfather, “there was nothing but swamps, crocodiles, and mosquitoes. The natives who roamed around here were very primitive, not like our Taínos and Siboneyes. The ones here were half-Indians, that’s why we called them Seminoles” (Todo tiene su tiempo, 119). It is difficult to live in a post-national space when exile is so similar to the island.

Works Cited

Bartra, Roger. La jaula de la melancolía: Identidad y metamorfosis del mexicano. Kindle ed., Ediciones Era, 1987.

Benítez Rojo, Antonio: La isla que se repite. Editorial UH, 2019.

Luque Escalona, Roberto. Masferrer en el país de los mitos. Ediciones Universal, 2017.

Martínez-Grandall, Kelly. Muerte con campanas. Suburbano Ediciones, 2021.

Aguilar León, Luis. Everything Has Its Time. Time to Cry, Time to Laugh, Time to Dream, and Time to Think. Ediciones Universal, 1997.

[1] Baquero said: “I have said more than once that the two greatest misfortunes in human history are the hands into which Christianity fell and the hands into which socialism fell. The Latins dramatized and distorted Christianity, either by nationalizing it like the Spanish, or by politicizing and commercializing it like the Italians; and the Slavs hijacked socialism and turned it into a monster in the traditionally tyrannical and enslaving mold of that people.” https://blogacademiaahce.blogspot.com/2020/01/una-carta-de-gaston-baquero-lydia.html