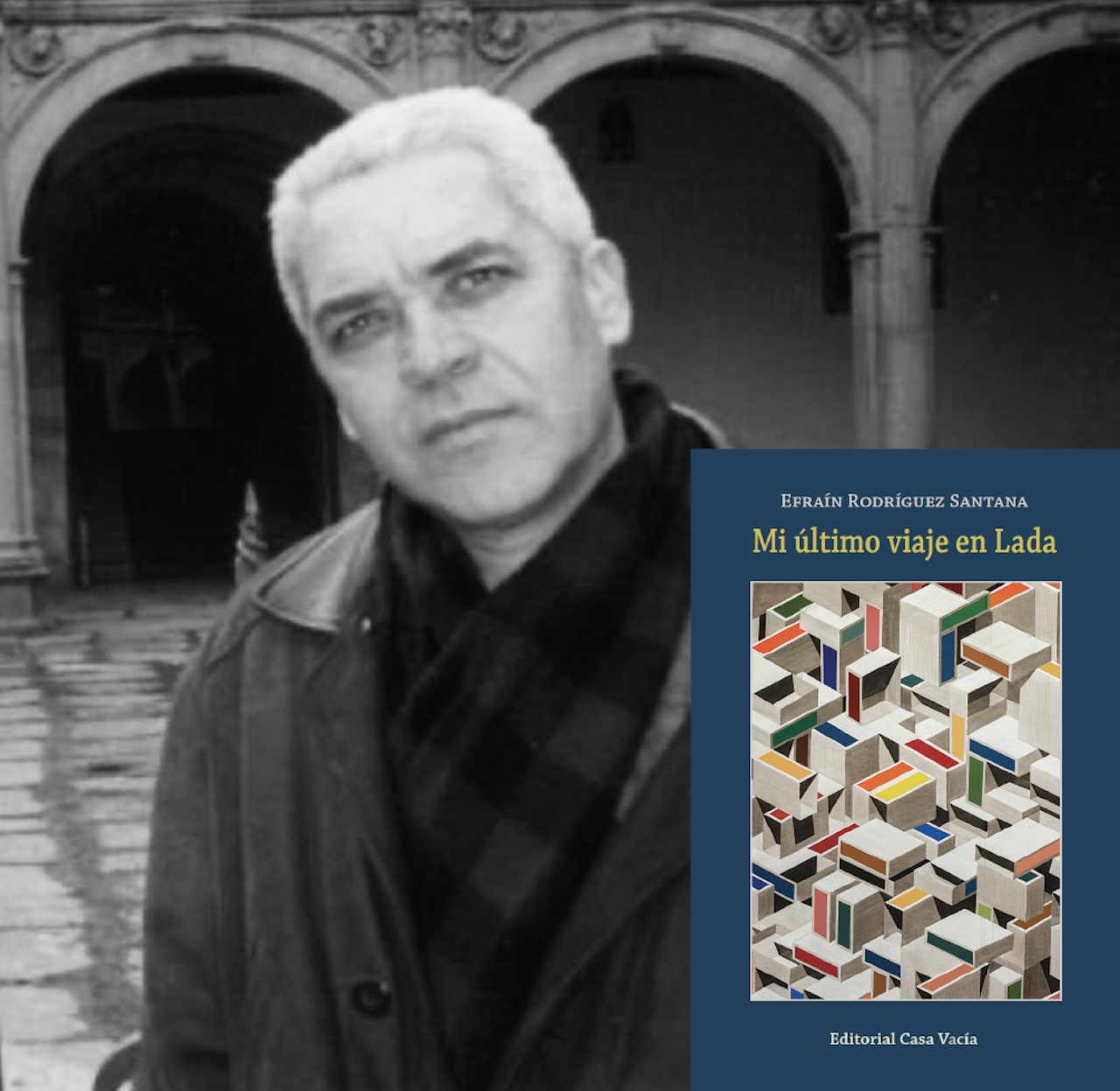

In Mi último viaje en Lada (Casa Vacía, 2025), Efraín Rodríguez Santana (Cuba, 1953) turns Havana’s ruins into a theater of memory, where the characters—poets, ex-convicts, agents of the Ministry of the Interior, shadows of the revolutionary past—engage in dialogue amid the corrosion of saltpeter and the delirium of suspicion. The book, the first volume of the Trilogía de Quinta Avenida, unfolds a plot that is both detective and existential: the theft of emblematic paintings of the Cuban avant-garde serves as the trigger for an investigation into guilt, surveillance, and the moral degradation of a country that has learned to survive between parody and fear. In a web of coincidences and returns, the novel pursues a truth that never allows itself to be captured, as if crime and literature were, at heart, versions of the same unfinished fable. In this dialogue, the author reveals the traces of that fable and the shadow zones that sustain it.

Mi último viaje en Lada combines elements of political thriller and crime novel with a vividly portrayed Havana backdrop during the so-called Special Period. What initially attracted you to exploring the intersections of crime, state power, personal relationships, and cultural life within this specific setting and genre framework?

The Ministry of the Interior is the institution that controls the life of an entire country; its powers are unlimited. It is shrouded in secrecy, and from there it articulates its procedures of control and punishment. We already know that, so what interested me as a writer was the inner workings of that institution.

Mi último viaje en Lada delves into the interior of that entity of absolute power and speculates on its deadly and twisted power rivalries. Those mechanisms of repression and surveillance become a novel.

Here, what happens outside is not as interesting as what happens inside. We are in the presence of an institution that protects the hardest and dirtiest secrets of the Cuban nation. And those secrets that people want to know about are speculated upon in Trilogía de Quinta Avenida, also composed of Nonadanadie and Bocanera. It is an act of imagination that is confirmed in reality.

There is nothing like the crime novel to expose that sense of legalized impunity of a closed patriotic surveillance system. What interests me is what happens inside that system, with characters capable of guaranteeing themselves immense secrets and power at all costs. A crime novel, I insist, as an act of imagination that is confirmed in reality.

Havana—from the decadent grandeur of Cisneros’ house on the Malecón to the relative elegance of Fifth Avenue and the somber functionality of Marina Hemingway—seems almost like a character in itself. Could you talk about the importance of these specific locations and the atmosphere of decadence and resilience you sought to evoke?

Havana, Fifth Avenue, the Malecón, the Playa district, Buena Vista, El Vedado, Marina Hemingway—these are the locations where the characters in this novel live and evolve. A dark plot and compulsive, sinister characters conspire and grow in the same environment and in the same direction: to repress, while trying to counteract any kind of mistrust that might “compromise” them. Mistrust, on the other hand, is an essential act of prevalence, of triumph, and also of condemnation. The members of this ministerial sect grow, rebuild themselves, disappear, sometimes leaving a trail of bewildering, cynical fury.

One of the two most prominent narrative lines in the novel refers to Cisneros, a poet recognized and recognizable by many. Cisneros bears the cross of his own fear, stands tall, makes deals with those who monitor and persecute him, continues a personal life that at times compensates for his dread, and forms special bonds with other characters such as Bocanera, Rod, Joaquín Mayo, and Negrón.

Cisneros’s house is a hole where everyone comes and goes as they please. It is on the verge of collapse, as oppressive as it is desolate, but he tragically clings to it, making all kinds of concessions and political juggling acts that he assumes are his only alternative for survival. His daily life is desperate, with thieves and police entering his house with equal impunity. What is Cisneros paying for? the reader wonders, and throughout the novel he himself will provide some possible answers to that question.

The novel presents complex relationships marked by ambiguity and hidden motives, such as the initial, almost mentor-like bond between Rod and Bocanera, the tragically revealed past friendship between Cisneros and his attacker, Negrón, and the intertwined professional and personal dynamics between W&Q. What role do these intricate, and often deceptive, personal connections play in driving the narrative and exploring its broader themes?

It is precisely in these ambiguous relationships that the best of this noir novel is concentrated. In such a sinuous context, the characters suffer from harassment syndrome, distrusting everyone and everything. No one will know anything for sure about “their comrades in arms.” What is evident today will be the opposite tomorrow. It is characterized and caricatured. It is a jumble of situations that fester on their own. And of course, people live at all costs to make the patriotic story fashionable. On many occasions, this reality of deadly appearances is questioned. It depends on how the stock is doing at the Bank of Persecution.

Among other characters, I like W&Q, miserable people with many resources for survival; Cabeza de Vaca, taken from a living sewer who is adored for his stench; and Guille, the neighborhood delinquent, subjected to real misery and real madness. Rod and Bocanera, practitioners of an ambiguous friendship, respect each other, are grateful to each other, and believe themselves to be the antithesis of other more or less miserable lives. Bocanera, in particular, is a character who could only be credible in literature, yet, given what we have seen with the so-called “daddy’s boys,” we could find him on any corner of El Vedado or Miramar, dressed as a MININT officer. Cata and Emilia are scary, attractive, destructive, and hard to kill. These characters rule the novel, along with others who split and recycle themselves throughout the trilogy.

Cisneros, the aging poet surrounded by art and literature amid crumbling walls, represents a particular cultural figure, apparently besieged by both external forces (thefts) and internal forces (his past, his fears). What do Cisneros and the world of art and letters he inhabits mean within the novel’s exploration of Cuban society during that period?

Cisneros is part of that 1971 retraction at the UNEAC. He tries to speak at that meeting, but what he says is barely understandable. It is the furor of events; the poets protect themselves as best they can, marking a deplorable milestone in the history of contemporary Cuban literature.

There is nothing triumphant about that meeting. It is from this point on that the public decline of all of them begins; they are watched, monitored, and removed from the cultural life of the country. It is something that will continue for many years, implanting itself as unavoidable resentment and perpetual defenselessness.

I place the character Cisneros at the very moment of the theft of his paintings in 1994, with all its devastating implications. He resists as best he can, an exemplary resistance, subjected to pedagogical censorship that will gradually fade with the awarding of the corresponding national prize, subsequent publications, and a few trips.

This is where Mi último viaje en Lada (My Last Trip in a Lada) begins. 1994 is also the year of the Maleconazo, the mass exodus of Cuban rafters to the United States, and the meeting of Cuban poets from both sides of the divide in Madrid.

Throughout the novel, the theft of the paintings and the murder of Negrón are revealed not as a simple criminal case, but as a reflection of deeper and older conflicts within the Ministry of the Interior. Reference is made to purges such as the trials of ’89 and secret groups such as the “Club de la Chaveta Comunista” (Communist Nut Club). Why was it important to connect a crime in the present with this hidden history of power in Cuba? What does this connection reveal about how the past and its secrets continue to operate in the present?

These are highly charged topics, very attractive from a literary point of view. And since this is a crime novel, the 1989 trials will be treated with complete freedom within fairly secondary narrative planes. I invented the Communist Chaveta Club to give greater prominence to systemic surveillance within the most sophisticated and powerful apparatus in the country.

The reader will see, I don’t want to give anything away, that this Club is always run by women, has superpowers, and is an open secret. The crimes of the moment are connected to the crimes of the past, the oversight of ministerial entities and some of their bosses who come into conflict with higher powers will pay for it. Here the characters rule, fiction is a palpable fact because everything is true. We must remember that these departments are lethal in their controls and guarantee absolute order.

The novel concludes with Bocanera forced to leave Cuba after a heartbreaking investigation that costs him the life of his lover, Boni, and strains his friendships, while the final fate of the stolen paintings remains ambiguous and the full picture of the forces at play is still murky. What final impression or question about truth, power, and survival in this context did you hope to leave the reader with Bocanera’s departure?

Bocanera is a victim of his father’s interests. That’s all I’ll say; I don’t want to reveal any more about that monstrous relationship between father and son. Ambition and terror go hand in hand in Bocanera’s life.

In him, we glimpse an inexplicable vocation as a spy, while his personal life is protected by a power to which he pays tribute with all his energy and intelligence. There is no naivety in Bocanera; he is one of the most nefarious characters in the novel, even though we feel pity for him at times. I speak now as a reader, not as an author.

In each novel of the trilogy, Bocanera, as the main character, grows in his appetite for power and in his human defenselessness. His cynicism is perfected, he matures more in his hidden purposes, he knows what he wants.

Crime novels and political thrillers have their own genealogies inside and outside Cuba. Thinking of Cuban authors who have explored themes of power, urban decay, disillusionment, or crime (such as Leonardo Padura and Amir Valle), how do you see Mi último viaje en Lada dialoguing with, or differing from, the Cuban novelistic tradition? Do you feel part of a particular trend, or are you seeking to break new ground?

That’s an almost impossible question to answer right now. We have to let the trilogy come out, and then we’ll know more about whether literary classifications and categories have any importance.