The assessments made by the Academy—histories, reviews, dictionaries—by the meager literary criticism in the media, and of course by the plundered Artificial Intelligence, pale in comparison to the simplicity of the books I have reread or wish to reread. My literary canon is usually based on rereadings. That is my point of view.

The rod that the Greeks (κανών, kanṓn) used to measure is still used today, metaphorically, without excluding its political and commercial pitfalls or other uses in music, religion, sagas… Although there is also a private, singular use. Perhaps fickle. Dependent on experiences, moods, friendships, stages of life, fluctuations in taste.

As is well known, inherited canons predominate… My experience, in this sense, is complex. Since my adolescence, I have been a teacher of Spanish and literature at all academic levels, from secondary school and pre-university to bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in Hispanic language and literature. so I have had to follow programs that are sometimes very strict, closely tied to cultural history or not developed by me, which have forced me to study texts, some of which I read with difficulty, even with a certain boredom.

From having to teach them so much, I have come to establish a love-hate relationship with some of these books and authors, to the point that I might even admit that I could have been wrong. Out of resignation and boastfulness, today I think they may be canonical. My reservations begin with myself, as they should. I tend to mock those of us who sometimes use experience as an argument, ignoring the fact that a mistake repeated many times does not become a success, a fallacy typical of gerontocracy.

I have tried—not always successfully—to ensure that my canon only contains works of literary art determined by El placer de leer (The Pleasure of Reading)—like that legendary magazine—or influenced by the title of one of my books of literary criticism: Leer por gusto (Reading for Pleasure). That is, for entertainment, without work or study obligations. Remember how sweet and useful Quinto Horacio Flaco taught us in his Ars Poetica (Epistle to the Pisones).

The patch goes ahead when I name, for example, the canon of Cuban narrative works. I have just reread several novels by Cuban authors: El reino de este mundo, Los pasos perdidos, El acoso, El siglo de las luces, and Concierto barroco, by Alejo Carpentier; Tres tristes tigres, by Guillermo Cabrera Infante; Paradiso-Oppiano Licario (they form a single, unfinished work), by José Lezama Lima; La vieja Rosa-Arturo la estrella más brillante (Two stories linked by a common theme) by Reinaldo Arenas… I may be forgetting some other novels, but I don’t think there are any others.

Such uncertainty reflects my admiration and affection for other writers from my country, but I have simply read them and not reread them, especially those from the most recent crop. I keep up with what talented writers such as Ena Lucía Portela and Martha Luisa Hernández Cadena are writing, just to illustrate the limitations of my own knowledge. I always want to read their new publications. Although—like any neighbor’s kid—it never crosses my mind to buy or request library services for the volumes of “stars” whose lack of talent is matched only by their relentless publicity campaigns. Here, the notion of canon linked by me to rereading could create a reverse canon, which would only include the worst Cuban novels, in order to be used to threaten some fool with the punishment of reading them; or more simply: not even take them into account, as is done with the avalanche of poems. And I won’t get into the short story. Although I would like to return to some of those included by Alberto Garrandés in Aire de luz. Cuentos cubanos del siglo XX, an anthology that is now a quarter of a century old and would require discussion of new values and updating in 2025.

I commit the sincere cynicism of saying that when I am asked about certain Cuban writers, I reply that I beg their pardon for my ignorance, but I have not read them—which is true from the second page—or I do not know who they are. A colleague says he prefers to praise them rather than read them; as Lezama told me about the “colloquial” poems of a well-known poet, as I recount in my autobiography, which I am writing with epigraphs by Emile Cioran and Karl Kraus.

If you open up the re-readings to the Spanish-speaking world—as is easy to imagine—the list becomes more controversial. Although not as flimsy as the one included by Harold Bloom in “The Democratic Age,” corresponding to Latin America, at the end of The Western Canon, which he claims to have written Roberto González Echevarría—his colleague and neighbor at Yale—where Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo and Juan Carlos Onetti’s La vida breve, among other simply essential Latin American works, do not appear.

I have reread—a commonplace—El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha. And also La Celestina (Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea). I will never stop returning to the enjoyment of La vida del Buscón llamado Don Pablos, ejemplo de vagamundos y espejo de tacaños, by the brilliant Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas… I will try to take similar delight in Fortunata y Jacinta by Benito Pérez Galdós, the Sonatas by Valle Inclán…

My canon—like that of any avid reader—is constantly changing. The timelessness of the gerund conveys the absence of an ending. The pleasure has multiplied over more than five decades. Also—before, during, and after—the major novels of the so-called Boom, I ask myself again which ones I would like to reread. I think that for now it will probably happen by chance: the ones you reread because you don’t have another book or you’re looking for a certain memory or reference… By Mario Vargas Llosa: The Green House, Conversation in the Cathedral… Or it may just be rereading a particular chapter or scene, such as the storm in the jungle in Canaima, the great novel by Rómulo Gallegos.

Since no one knows when they will be called to outer space, perhaps I will have time to reread novels, essays or parts of them, decisive passages from the Delphic Course, my favorite poems… In this sense, it is obvious that age does not grant you the face of a kindly grandfather or turn whims into chance occurrences. And forgive me for the lists. They are another form of summer languor.

Invoking love for flexibility—of course—does not justify the relativism of mediocrities and opportunists. Questions about reading do not call into question Raymond Chandler, Wallace Stevens, Federico García Lorca, or César Vallejo, to name the first ones that come to mind. They do not play with the color with which one looks, that cheap trick of cheap writers who cheapen themselves.

Perhaps it is a rhetorical ploy to insist that my view has never been rigid. Perhaps the test of rereading is just one argument among others, like writing a review. Perhaps they are nothing more than questions, especially about the precepts derived from any canon. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps; like Osvaldo Farrés’ bolero.

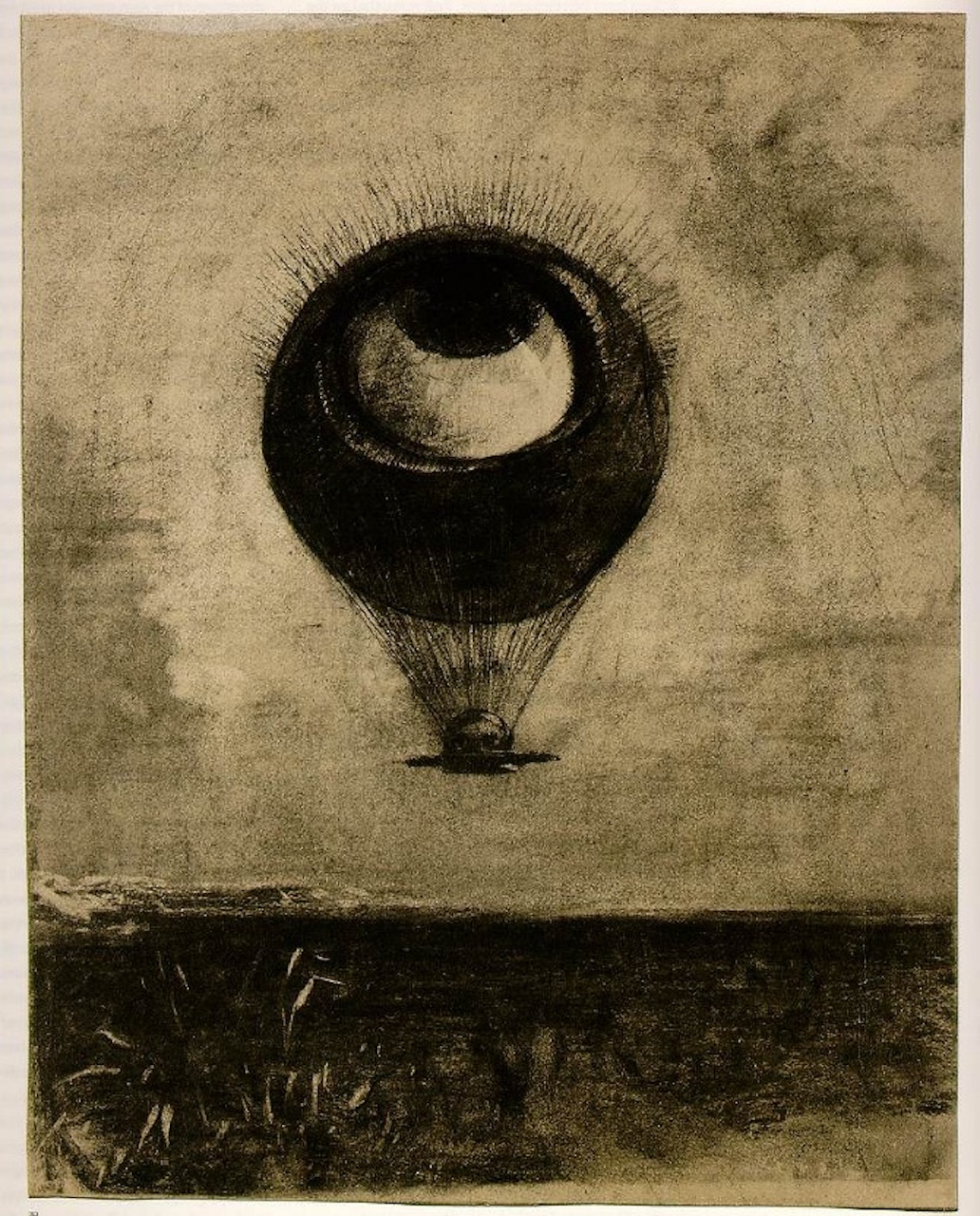

Image: Eye-Balloon (1878), by Odilon Redon.