To approach Malincuor is to assume that one has been summoned to a clandestine reading ritual in which each carriage of the Europa—that train that does not travel alone, but carries fragments of history, affections, and absurdities—functions simultaneously as a domestic archive and an epistemological springboard¹. It is not mere density: Medo constructs a space in which chronologies are suspect, harmless objects betray memory, and returned letters are ironic epiphanies².

“I was born in the last carriage of a train called Europe”³ — with this opening sentence, Medo inaugurates a cartography in which exiles do not end on land, but continue within the book itself.

My own initiation was absurd in terms of reading: while reading Transtierros in Buenos Aires, I tried — not once, not twice, not three times… but five times!⁴ — to send contributions, all of which were rejected with the same courtesy that an unusual manuscript deserves.

Each return was an early prelude to the average experience proposed by Malincuor, where persistence and active reading intertwine in a game of post-memory and processing of the real. Medo is not only a poet; he is a cartographer of the invisible, an architect of memories, and a master of linguistic artifice.

Archaisms, deployed as nods to attentive readers, are mixed with contemporary slang to produce a kaleidoscopic effect: one laughs and learns at the same time, while each chained subordinate clause and each digression acts as deliberate resistance against linearity.

“Dad broke the keys on the old Remington”⁸ — the familiar scene set by Medo demonstrates not only the fragility of language, but also memory made tense.

The text establishes a double historical discourse: European history and family microhistory coexist, intertwine, contradict each other, and illuminate each other⁹.

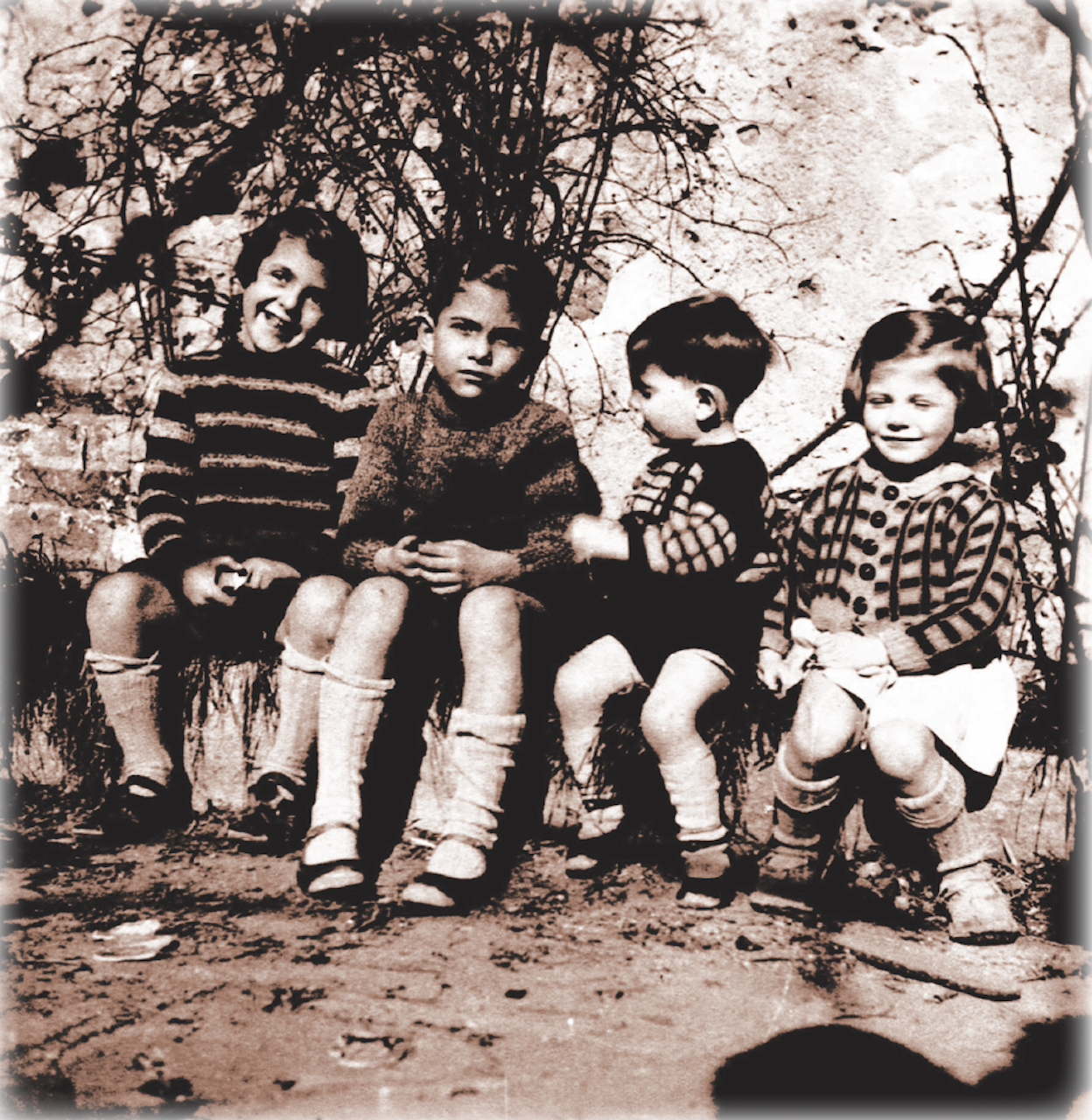

Each returned letter, each blurred photograph, each trivial object — playing card, sticky note, old machine — functions as a temporal portal. One never reads Malincuor without feeling that history escapes, mutates and, at times, mocks oneself¹⁰.

“Language, he thought, is useless if what one seeks is to know the truth…”¹¹ — here Medo explores the tension between language, truth and fiction, emphasising that truth is not a possession but a process of permanent displacement.

This is not simple nostalgia or mere biography. Malincuor is an artefact of artifice and complicity, where accepting that reading is travelling becomes a condition of reading. The density, humour, archaisms and current slang do not block: they activate critical attention¹² — we do not write for those who want clear routes, but for those who want to lose themselves with delight in labyrinths of meaning.

Scholarly critics — Tamara Kamenszain, as well as Eduardo Milán, Berta García Faet and, especially, Vicente Luis Mora — point out that Medo reconstructs time as a palimpsest: affections, objects and archives intersect, causing epistemological dizziness and complicity with those who dare to follow the rhythm of the carriages.

“Forgetting does not erase, it obscures”¹⁴ — with this sentence, the book articulates its strategy of memory: not to erase, but to make visible the twilight where history, trauma and laughter share space.

Post-memory is not incidental: it is an active axis, a mediation that allows us to understand how Medo’s story is inscribed in History without reducing it to a mere factual archive. Letters, blurred photographs, sticky notes and the Remington function as agents of historical and emotional transmission¹⁵.

Each syntactic twist, each chained digression, each leap in linguistic register constitutes a conscious challenge: the reader who allows themselves to be carried away enters a universe in which history is not narrated, but experienced, where the baroque and the playful intermingle and where archaisms and contemporary slang generate a conversational rhythm that seems trivial, but constitutes Medo’s very signature¹⁶.

“The truth is that we were a family”¹⁷ — here the tension between the global and the intimate is condensed into a truth that only poetic language can articulate.

Malincuor is not just a book: it is a critical artefact, a laboratory of density, humour and erudition, where irony, complicity and criticism converge¹⁸. Here, one does not learn to read Medo; one learns to exist between trains, letters, and memories, accepting the illusion of linear routes as part of fiction, not experience¹⁹.

To read Malincuor is to enter a semantic field in which history is no longer a static past, but a process of tension between memory and writing, between family and grand History. It is learning that language does not tell the truth, the plot; that memory does not erase, it obscures; that post-memory is a fiction in which the reader becomes the co-author of their own History. Moreover, to read it is to accept that literature is not a mirror, but a space of radical displacement, where the coexistence of humour and irony with profound meanings turns any reading into a vital experience.

Some notes

¹ Each carriage of the Europa functions as a laboratory of temporal simultaneity, a node of collective and private memories, and a possible springboard for interpretative vertigo.

² Density is not an obstacle: it is a mechanism for inducing active reading and erudite humour, comparable to searching for Wi-Fi in an old carriage.

³ The opening sentence of Medo articulates space-time: it is not hyperbole, it is sentimental geography.

⁴ Rejected attempts at collaboration: five; metaphorical correlation with the carriages and the plural time of Medo; the irony is that each rejection taught more than any publication.

⁵ Post-memory as a ritual approach: a reminder from Hirsch (1997) that remembering what one has not experienced can also hurt… or be fun.

⁶ Archaisms + contemporary slang = an intellectual cocktail that induces complicity and semantic hangovers.

⁷ Chained subordinate clauses and digressions: deliberate resistance to linear reading; they also serve to tell private jokes between author and reader.

⁸ Familiar scenes: combining humour, trauma and language learning; a whole educational programme disguised as an anecdote.

⁹ Double historical discourse: coexistence of macro and microhistory; chronology vs. kaleidoscope; for readers who enjoy getting lost and finding themselves in the same thing.

¹⁰ Objects as temporal portals: bookmarks, sticky notes and blurred photos function as historical witnesses and laboratory jokes.

¹¹ Reflection on language and truth: Medo ironises about the craft of writing itself while making us accomplices.

¹² Density activates criticism: there is no reader GPS; only multiple itineraries.

¹³ Critical echo: Kamenszain, Milán, Santiváñez, Mora, García Faet; all confirming that Medo provokes epistemological dizziness, but with class.

¹⁴ ‘Forgetting does not erase, it obscures’: a statement that combines coffee bar philosophy with academic rigour.

¹⁵ Post-memory and objects: historical mediators, narrators and occasional shelf destroyers.

¹⁶ Syntactic twist and slang: author’s signature; sensory and cognitive training guaranteed at no additional cost.

¹⁷ Global-intimate tension: philosophy of train carriages and kitchens, simultaneously.

¹⁸ Critical artefact: density + humour + erudition = controlled explosion of the senses.

¹⁹ Existing between trains, letters and memories: reading as a vital and political adventure.