Since that furtive encounter at the old Kendall Art Center, Lisyanet Rodríguez’s work has revealed itself to me as a form of knowledge that transcends the sensible. Plato was right when he asserted in The Republic that “art is but a shadow of a shadow,” and yet, in Lisyanet’s work, that shadow acquires ontological density, becoming a form of truth that cannot be spoken, only contemplated.

In 2018, I attempted to capture that truth in words in an essay for CdeCuba Art Magazine No. 25. I dared then to name the ineffable: “cronopios, indefinable characters, subtle flashes”; that was also a dialogue that intertwined an argument with the figuration of Maikel Domínguez, another artist who, like Lisyanet, seems to inhabit the threshold between the visible and the invisible.

Time has refined Lisyanet’s aesthetics into an experience of extreme delicacy. Her pictorial universe places us in a post-apocalyptic scenario where emptiness—“nothingness is not simply emptiness, but the radical negation of being in its entirety”[1]—is not absence, but an unsettling presence, as is often the case in the work of Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Anguish ends up twisting the beams that atrophy the bodies.

Far from representing, Lisyanet interrogates a world from the perspective of atrophy, disability, and ontological decomposition in order to reconfigure it from a sensibility that borders on the metaphysical. She does not seek truth—like Octavio Paz—but revelation.

If her large-format canvases resonate with the roar of disturbance, the scars veiled by clothing, the lacerations of body and soul accentuated by the harshness of the flat backgrounds, her drawings reveal an interiority, a pain, without hope. There is no consolation, no promise of redemption: only pain, naked and persistent. Lisyanet looks, with a lucid gaze, into the abyss of the residual, at ruin as a vestige of the human, and in that desolation she finds a delirious beauty, a trembling light that insists on shining from the darkness.

If dismembering a work—as a whole—has always been a vestige of a culture that has found in fragmentation a hedonistic dose for the consecration of a discipline, Lisyanet’s work is a symbiotic unity, a living body that is transfigured, an entity that pulsates in its symbolic reorganization, revealing a face that is not a face, but a transition: like the sand that draws an ephemeral face on the shore, only to be erased by the tide. Foucault warned of this in The Order of Things: any attempt to define the human is doomed to vanish, like that face of sand that the sea reclaims without memory.

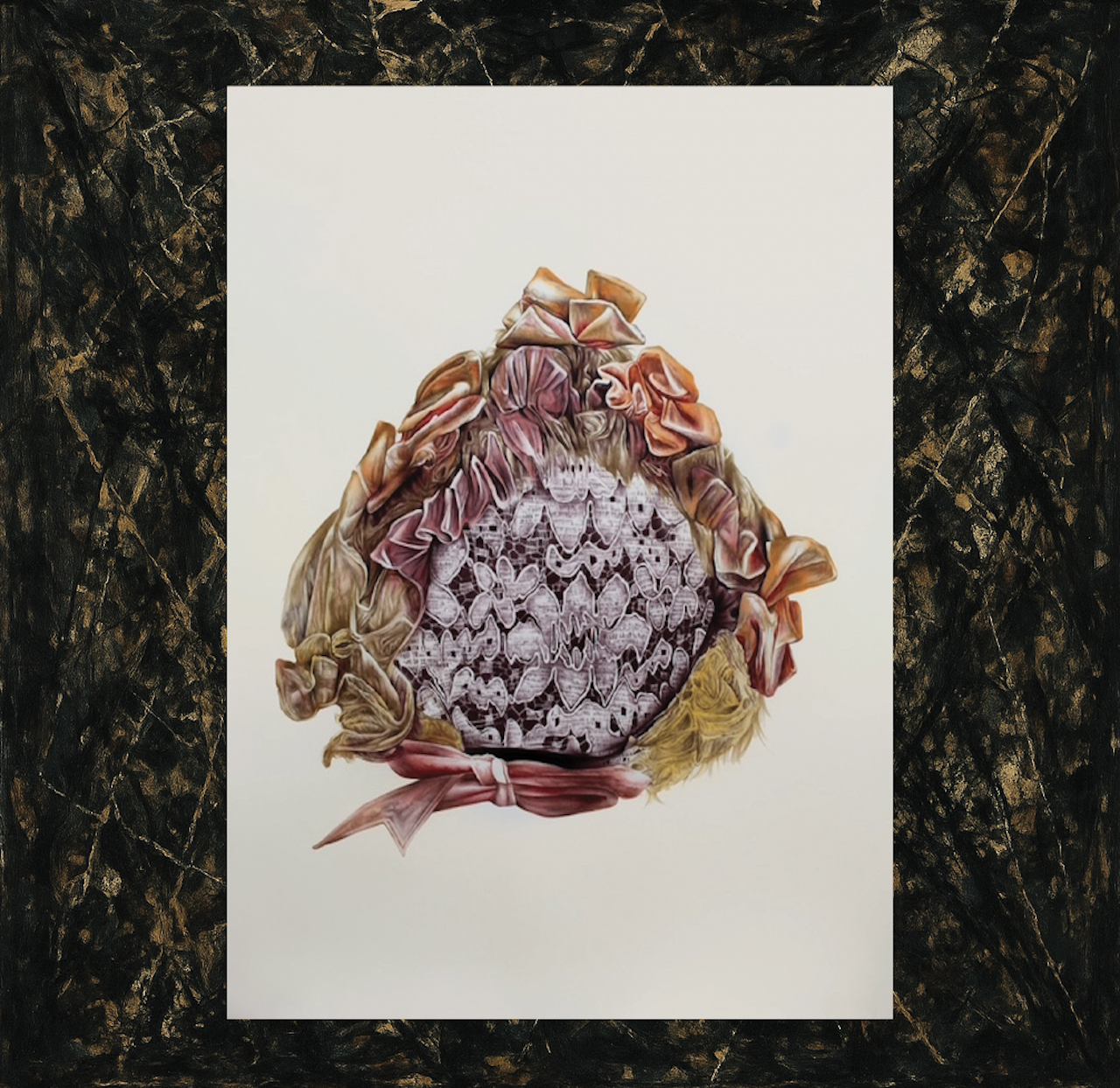

The meticulous drawings that make up the series Dressed Up are not only a turning point in a work riddled with lucid melancholy, they are the vestiges of a spiritual transition, arabesques frozen on the threshold of time and despair. Lisyanet Rodríguez, possessed of a prodigious hand—at a time when so much gestural banality prevails in contemporary art—has learned to dialogue with shadows. In an almost liturgical gesture, she opens the chest of memory—that coffer anointed by the effluvia of blackened cedar, where time has embroidered its signs with indelible ink—and, as she dusts off its contents, she seeks not to restore what has been lost, but to invoke the spectral presence of what once was. Each stroke, each fold, each hint of form, is a reverberation of the past that manifests itself as a whisper in the darkness, like an oblique light that reveals the secret texture of things. Lisyanet does not delve into the past to paint, but to conjure; she does not do so to represent, but to resurrect.

Duration—that invisible substance that Henri Bergson knew how to name the soul of time—adheres to things with a gravity that crushes them, densifies them, turns them into ontological relics. In its thickness, absence is prefigured: the body that was and is no longer, but whose trace persists like an echo in matter. Lisyanet Rodríguez, with the gaze of an alchemist scrutinizing the signs of the beyond, delves into the remains of a symbolic tomb, not to desecrate, but to restore to those fragments the dignity of their first light.

What emerges are not mere garments: they are the attire of others, the clothes that still inhabit houses like gentle specters, like embodied memories. It is the wedding dress of the dead grandmother, which still exudes the perfume of jasmine that never fades; it is the white tunic that envelops the body of Remedios La Bella as she ascends to heaven, like a vision suspended between flesh and spirit. Each garment is a reliquary, each fabric a prayer, each thread a line written by time in the secret book of lived experience.

And in this gesture of evocation, memory reveals itself as an act of resistance against oblivion, that slow shipwreck that threatens to erase the contours of the beloved. Remembering is not simply preserving: it is reviving, it is breathing into the object the dignity of its history, it is challenging the erosion of time with the tenderness of one who knows that everything that has been deserves to be looked at again. Oblivion, for its part, is not absence, it is imposed silence; a shadow that falls over what is not named. Lisyanet, by naming with images, by dressing the invisible, turns her work into a spell against that shadow, into a liturgy of permanence.

Lisyanet Rodríguez inhabits a time that is not the present; it is the echo of a past colonized by melancholy, not as nostalgia, but as dignity. She does not reclaim it, she transfigures it. Her homeland is not geographical, her homeland is memory: the invisible territory of what has been lost, what has been taken away, what still hurts in the silence. Her work is a journey—not of physical exile, but of the soul—towards the vestiges that the body has kept as scars. There lie the guilt, the pain, the wounds that never fully healed, the anguish that is breathed like stale air, the plague that, as Camus would say, reveals the human condition in its rawest nakedness.

Lisyanet Rodríguez does not walk through time, but through its rubble; she inhabits a past that she does not claim, but which envelops her like the warm dust of a city besieged by silence, which is why her backgrounds are flat. She does not long for the past, she elevates it, turning it into sacred matter. Her homeland is not the earth, but memory: that invisible territory where “all that man can gain from the game of plague and life is knowledge and memory.”[2]

Her work is a descent into the body, a journey into the bowels where history has been tattooed with fire. There, guilt slips like thick oil over the skin, pain is chewed like stale bread, and wounds—closed with thread of shadow—ooze images that cannot be named. Anguish settles like a nocturnal animal in the chest, and the plague—that plague that Camus saw as a mirror of humanity—becomes revelation.

As in Oran, the city where “the plague is not tailored to man, therefore man tells himself that the plague is unreal, it is a bad dream that must pass”[3], Lisyanet turns exile into language and the body into an archive. Each brushstroke, each line, each sketch is a fallen mask, a held breath, a wound that sings. Her work does not seek consolation; if anything, it confronts us with the density of that memory, everything we have abandoned in an attempt to be happy. Lisyanet Rodríguez paints so as not to forget, to resist, to name the unnameable. Her work is not just image: it is an act of preservation, a gesture of rebellion against oblivion.

Dressed Up is an exceptional series, its pictorial delicacy clouding the gaze, as if the memory were filtered through a damp veil of childhood. Like Amélie, who discovers a metal box crammed with forgotten objects between the walls, Lisyanet takes us back to that intimate space where memory has a smell: warm metal, aged paper, dust that holds secrets. She takes us by the hand back to childhood, to that place where time is not measured, but felt. Because, ultimately, memory is not a static archive, but a living body that breathes, that hurts, that transforms. It is, as Camus would say in The Plague, knowledge and memory are the only things that can be gained in the midst of absurdity. In Lisyanet’s work, remembering is not looking back, but holding on to the present with dignity. To paint is to resist the wear and tear of time, to affirm that what has been lived—even if fragmented, even if wounded—deserves to be named.

Lisyanet Rodríguez’s work is a meditation on ontological fragility, the persistence of humanity in the face of the ravages of time, and the urgency of preserving that which ultimately proves elusive. When technological speed threatens to erase what is essential, when banality takes hold of individuals, when hysteria reigns as behavior, when illiterate individuals only consume short messages and only what does not hurt their fragile sensibilities, Lisyanet reminds us that memory is neither a luxury nor nostalgia, but an ethical necessity.

Notes

[1] Sartre, J. P., & Valmar, J. (2012). Being and Nothingness. B-Iberoamericana. P. 234.

[2] Camus, A. (1990). The Plague, (vol. 35). Libresa, p. 87.

[3] Camus, A. (1990), p. 53.