For Axiom de Litera, anyone who tries to be intellectual is not, and no one can be what they are not; this is due to the punctuality of reality, which lengthens the moment more efficiently than Zeno’s paradox. This commonplace is, however, so subtle that it often goes unnoticed by those who strive for style, ignoring that style is not expression, but rather the architecture that sustains it, in a thick and inviolable metaphysics.

This maxim of Litera does not hide the bitterness of the CEO, but there is something there that explains the stubbornness of his distance; and that makes him always say the same thing, that style is nothing but the structure that determines naturalness. Thus, in another truism, if the gesture is affected, then it is no longer natural, and the object it describes will lack reality; therefore, no matter how bitter, it is a good parameter to avoid the hassle of late disappointment with an early one.

Namely, this is exactly the weakness that dissolves Surrealism, spreading it over so many generations; making a canon of the anti-canon, in a laughable and comical scholasticism, although pathetic and not hilarious in its emptiness. It is not that the first Surrealists were not authentic, but that they were the last to be so; for all the others were no longer authentic but wanted to be, locking themselves into Axiom’s paradox.

Continuing with the example, it is not that the authenticity of Surrealism was not deceptive, concealing its object; which does not consist in being surrealist but in not being realist, and is impossible to achieve if it is assumed as reality. This is obviously another paradox of Litera, becoming omnipresent in the pathos he rejects; but with which he recognizes the authenticity of early surrealism, as stupor in the face of the times in which he lived.

This makes the strange surrealist ways understandable—even Pythagorean—as a vulgar dislocation; but it casts doubt on all subsequent efforts, as an attempt at instrumentalization, which already dissolves that object. Hence the impossibility, more stoic than Zeno in the worst of his paradoxes, which is that of Achilles and the tortoise; bad as the art of later surrealists, because it ignores in sophistry the relativity of passage, and that is serious.

Nor is aesthetic blasphemy the preserve of the late surrealists, who are only a lesson for Axiom; rather, it is falsehood as the second nature—still natural—of all postmodernity. In fact, that dislocation of the early surrealists was not that of the surrealists, who did not yet exist in their stupor; rather, it was the imprint of the era, crossing the ultimate limit of modernity, toward the abyss; which was not contemplative but indifferent, because it already had other things to desire, such as quantum indeterminism.

Thus, in the same circle of late surrealists, late idealists debate with the same pretentious pathos; above them, Axiom de Litera casts a dismissive glance, for some strange reason, there is no surprise for Axiom, who hastens his steps to where he senses his virginal motive, intoning the monotonous litanies of true beauty. It is also true that everything was predictable, but only from that stunned disorientation that still tinges the naivety of those early surrealists with sincerity; all the more reason for this visceral rejection, with which the latecomers of everything can divert him from the only reason he breathes.

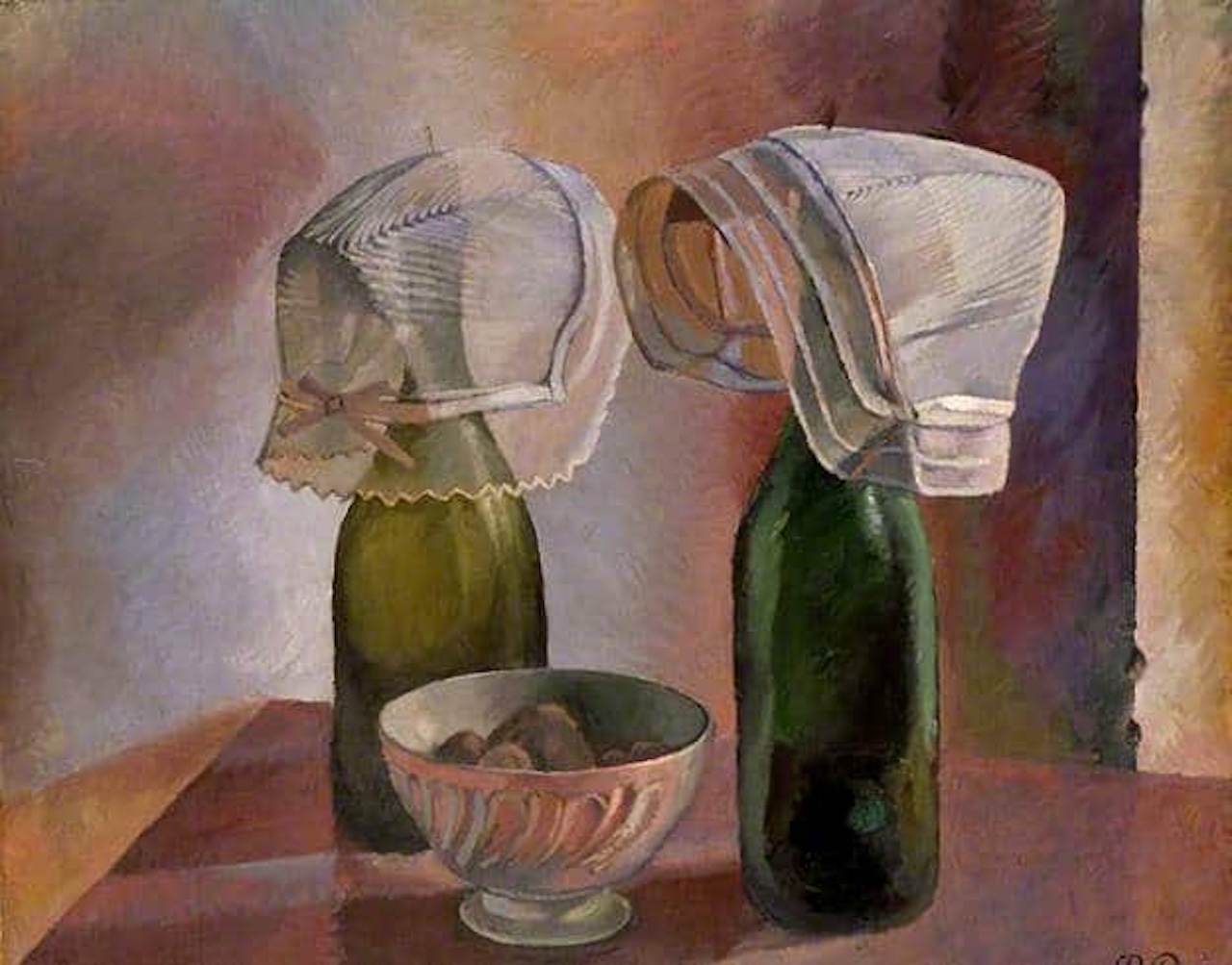

Image: Still Life with Bottles and Breton Bonnets (1924), by Pierre Roy.