Some pieces of music are displayed like diamonds in a showcase, while others, like family heirlooms, are tucked away in a jewelry box. Johannes Brahms’ late Intermezzos belong to the second category, although they have learned to be valued as if they belonged to the first. They seem like confidences whispered in the fumoir of a Viennese palace, when in reality they are treatises on sentimental metaphysics. It is worth remembering that behind all this soothing mist lies the ingenuity of a craftsman who knows that melancholy, when well packaged, becomes a luxury item.

Imagine the Maestro, an illustrious sixty-year-old, while the Vienna of the time dances waltzes as if time were a mere chronological frivolity. Brahms, true to his enlightened bearish nature, declines the invitation to the feast and decides to write, on lined paper, little love letters to his own shadows. Three opuses—117, 118, and 119—are thus conceived: sonorous epigrams, domestic variations on what he called “lullabies for my demons.” The adjective “late” serves as his alibi: everything that arrives out of time enjoys the privilege of mystery. As Nietzsche well knew, all evening thoughts take on an irresistible twilight glow.

The publishing strategy was worthy of a speculative count: Fritz Simrock published them in Berlin, shrouded in an aura of living relic—a curious anticipation of postmodernity, where a work still warm is sold as if it already smelled like a testament. The result: miniatures that boast formal asceticism and yet function as broad-spectrum affective catachresis. Anyone who plays the Intermezzo Op. 117 No. 1 must dose the pedal like a nobleman lowering his voice behind damask curtains; anyone who tackles Op. 118 No. 2 will discover a topography of modulations that reverberates through the carpeted hallway of a Hanseatic castle. These are subtle touches for performers who, if they miss a single filigree, transform the guided tour into a funeral elevator ringtone.

The cliché of Brahmsian “consolation” is often invoked. Allow me to disagree: far from “comforting,” Brahms sublimates. The listener, flattered in their vulnerability, does not know whether their pain is their own or an emotional prêt-à-porter tailored by the composer. Therein lies the cunning: transforming introspection into symbolic capital, an alchemy that fin-de-siècle salons and today’s auditoriums continue to capitalize on.

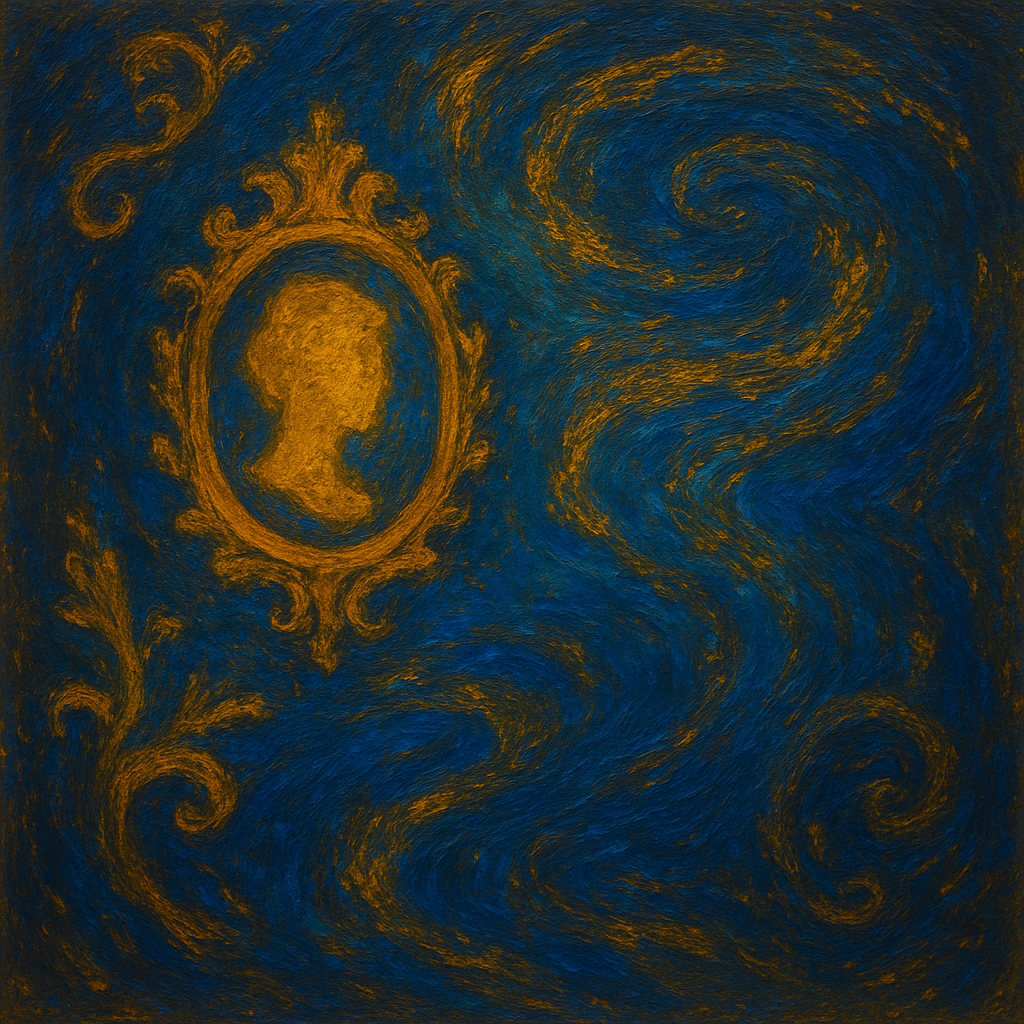

It is therefore worth reading the small print, as the Intermezzos are cameos. Those looking for Wagnerian epic will find, instead of Valkyries, the sigh of Meissen porcelain. Each piece opens a cabinet of curiosities where harmony, instead of displaying its treasures, hints at secret passageways through avoided cadences and chromatic delays. Listen to the closing pianissimo—that nineteenth-century fade-out—and you will understand that Brahms is declaring war on grandiloquence.

By bringing the music from concept to keyboard, these pieces become intimate portraits. Radu Lupu turns Op. 118 No. 2 into a whisper, where the pedal seems to make the harmony levitate without clouding it. Wilhelm Kempff illuminates everything with an almost liturgical clarity, sober in his use of the pedal and attentive to the breathing of the phrases. Emil Gilels polishes the sound until it becomes a dense amber, controlling the mezzo piano with the precision of a goldsmith. Claudio Arrau imbues it with a profound solemnity, with pauses that allow the complexity of the notes to rest. Murray Perahia sculpts a smooth melody that reveals the inner voices as if they were made of glass, while Julius Katchen, more architectural, accentuates the rhythm without the piece losing its perfume.

And then there is Glenn Gould. In his recordings, he approaches these Intermezzos with the precision of an entomologist: austere pedaling, a clean attack, and a millimeter-perfect rubato. He turns them into little inventions for two or three voices. It is a fascinating “Brahms read by Bach” that transfers the emotion to the counterpoint, leaving the listener faced with the very anatomy of melancholy.

In short, these Intermezzos are pocket vampires. They feed on our desire for transcendence while forcing us to pose as aristocrats of despondency. But if you have the necessary chic spleen and enjoy displaying that melancholy as an adornment, go ahead: all it takes is a click, a glass of Burgundy, and the intimate conviction that sadness, embedded in the piano’s song, can attain the status of fine jewelry.