Borges

More than a man of letters, he was Literature; more than books, he was the Book. Having read everything, he was the Reader.

Bosch (Hieronymus)

Bosch cannot be deciphered except fragment by fragment: the whole is nothing more than a pavement of keys in front of a closed door that none of them can open.

Blake

Two verses by Blake, to leave everything undecided:

How can the bird that is born for joy

Sit in a cage and sing?

Catherine of Siena

Oh, Caterina! I would have adored a daughter with your name…

Her beautiful name, which recalls –Katharòs– impossible purity, combined with that of the most beautiful Tuscan quote, can be repeated as a point outside the world, in search of freedom and silence.

It is useless to look for her in history, she did not even touch it, her cell is beyond the walls of the world. Trembling, I raise my eyes to the vision of glory painted by Andrea Vanni, the enchanting word of the highest Tuscan who ever descended directly from heaven to earth (and whom only Tommaseo seems to me to have understood) shines forth, transmitted in a bundle of parchments sent here and there, to convents and palaces, and I dare not knock on the door of the cenacle, one of the places where the absolute Transcendent has come closest to human souls, through a feminine musical instrument.

Catullus

Catullus is a poet of interiority, but his interiority appears polished like a surface. The internal organs sunk in their physiological evil, the smoking lips, the cloacal centers of the soul, yield under his hand their strangeness and their disorder of depth.

Céline

Céline brutally avoids wasting time, infecting himself with a word as if with a necklace, distancing himself from truth, emotions, music, life, and death.

Céline has died, condemned, of a satirical disease. No face seems more satirical to me than his, with the cancerous Muse stamped on his face. After Voyage, an initiatory poem in which Satire already touches the limits of Night, Céline’s vision shifts towards the pathological; the style, at times, moving from a thought contracted by illness, becomes part (no longer mere indignant contemplation) of evil, encourages it, opens breaches for it. He is a marked titan… In the intervalla insaniae, Céline is the true satirist: he confronts evil with the force of a hurricane and the impotence of childhood; his is already the indefinite satire of the world set ablaze.

Cioran

Something in Cioran immediately makes one sense a miracle: his language. An unpredictable conceptual density descends like lightning on the listening mind, leaving at the edges of the charred commonplace a slow echo of nocturnal melody that fades away, gliding.

Donne (John)

The architecture of all his love poetry is that of a cathedral, and only if one imagines a cathedral as a place empty of love will one’s attention be distracted, like an Orpheus without Eurydice, from the splendid verses for Anne More. The wise poet disdains to leave the sacred perimeter of the cathedral of love, discovering the disordered beating of passion: “joy is profaned / revealing this love to the secular.” In the sacrament of sexual union and in the achievement of an indestructible neutral unity between lovers, the absolute of love is found, and it is a model of fearsome height: for us, incredulous and torn apart, the vision of this dead man and this death captivates us.

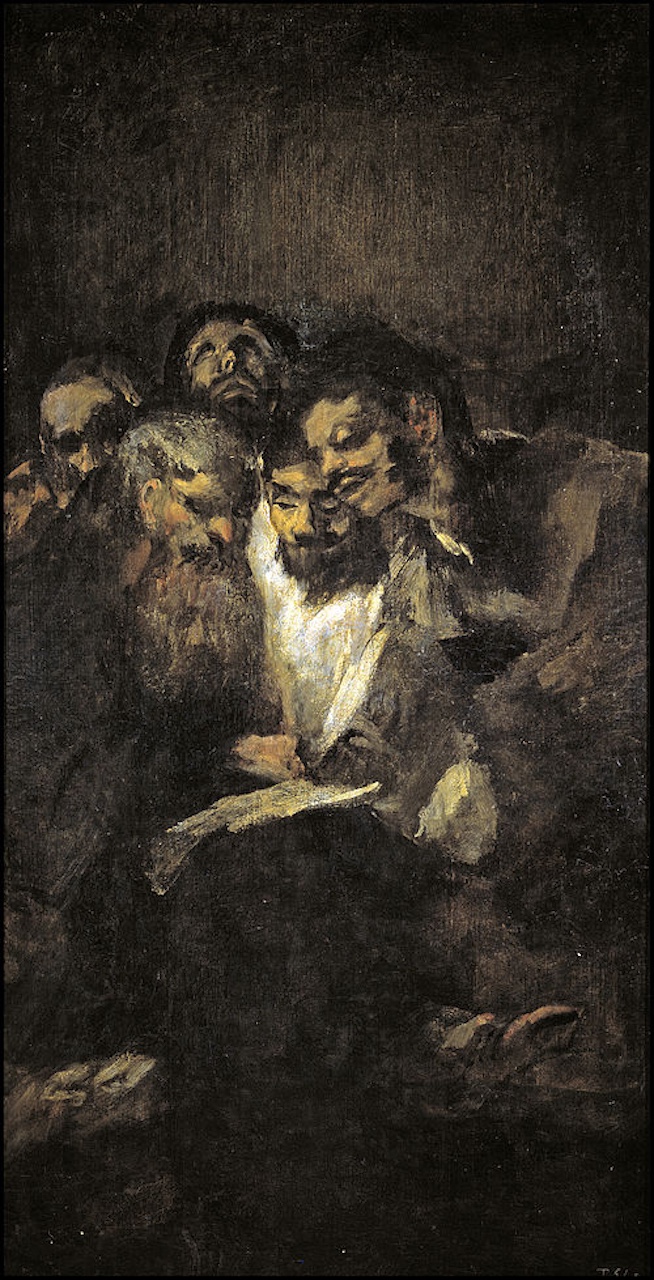

Goya

None of his biographies will tell us at what moment, in the temple of his skull, in his mind inspired by the deepest cosmic depths and ravaged by human compassion, the whole earth and the history of man, the meadows of San Isidro, Robespierrists and Bonapartes, Inquisitions and Manzanares, prisons and distant islands, councils of the Philippines and restorations, revealed themselves as exterminated anthills of an evil kingdom.

Goya was aware that he was painting nothing but masks, sometimes alive, sometimes dead, and he poured all his talent more into the clothes than into the faces, as if he were superbly dressing large dolls. Hence his mugnechismo, in mysterious accordance with what Ortega says: that Spaniards have no real interest in their fellow men.

Heidegger

Heidegger, lost within his Greco-German Seinvergessenheit, has not wanted to remember that Being, in the Old Testament, at no point becomes Forgetfulness of Being: if it appears veiled, if it hides its face, it is because its uncovered face can kill. Hebrew is a violently ontogenic language, the language of being…

Hernández (Miguel)

Miguel Hernández was the last poet capable of eliciting true tears, unique among his sterile contemporaries and far removed from the tearful. His Castilian verse is undeniably modern, because of the new insights it reveals to thought and analogical fury; because of the shot of passion straight to the listener’s heart, it is Spanish without the españolada.

Hitler

The world reflected in Hitler’s eyes is that of the shadowed face of the universe. More than the will to power, his gaze expressed the infinite sadness of a beaten dog: it penetrated men and women through the remorse of a blow not inflicted. Demonologists know satanic sadness, the sadness that emanates from denial and destruction. Hitler’s canine sadness well concealed his complete devotion to his infernal master.

Hölderlin

Hölderlin speaks of the stars as sisters, dolls, and dogs of childhood; the silence of the stars is familiar to him, while human speech is incomprehensible.

Kafka

Kafka is a carpet made of all the threads and colors of mystery and Hebrew passion; he is prophetic and Talmudic, a traditional choice and the decadence of a ghetto about to be demolished, a scapegoat and Zionist tikvà. It is a flying carpet that allows us to rediscover, after the night flight, the familiar architectures of the metaphysical absolute, which, even when suspended and floating, seem to alight, alone, on solid ground.

Kafka is a veiled revealer; through his strange denials, the persistent illusion, the Hebrew hope, sends, as if from a sea of fog, a lost ship, some hoarse sound of danger and consolation.

Kant

In the biography of the Russian Arsenij Gulyga, I find him described as follows: “Kant was 5’2” tall and had a fragile air; he diligently resorted to tailors and hairdressers to appear elegant; he liked his light blond hair, blue eyes, broad forehead, and bearing.” Unlike Leopardi, who loved the démodé, Kant closely followed fashion. Tricorn hat, powdered wig, cinnamon-colored frock coat with a black bow, gold braid and silk-covered buttons; waistcoat and breeches of the same color, white lace shirt, gray silk stockings, shoes with silver buckles and a sword at his side.

The biographer refers to a gallant letter written to him by a beauty from Königsberg, then twenty-three years old (married for ten years), on June 13, 1762, inviting him to a meeting. The letter said: “My clock will be wound.” Tristram Shandy, the success of the time, recounting his father’s story, says that for him “winding the pendulum” was the signal, for his mother, of the conjugal act. It is a relief to know that Kant did not live in absolute monaxìa, barely perfumed with personal elegance, without the light of women, and that women’s watches and pendulums were wound and rewound for him. (“Man cannot enjoy any pleasure in life without woman”: ipse dixit). But perhaps he turned down that date…

Kavafis

He lived in the shadows, and the light of the candle attracted shadows to his home, the ghosts that fed his verses.

In Kavafis, concentrated morbidity is unattainable, due to his cult of enclosed space, of pleasure as deprivation of external light. An atmosphere evoked by Kavafis is erotic even if one imagines it perfectly empty.

For him, the voices of the dead are like nocturnal music fading beneath the house. The clatter of pots and pans and bottles, a few notes from an accordion, seem to him like Dionysus’s retinue abandoning Antony and his fortune.

A characteristic of the homosexual myth is to always see the victim, the dead person who is mourned, as beautiful. It is pure myth; victims and dead people are rarely beautiful. Kavafis mourns the eternally unchanging beauty of a dead god, which was surely not in the coffin he mourned.

Leonardo

In Leonardo’s self-portrait in Turin, one also reads a sorrow for himself for having let the unity of thought slip away, for having fractured his mind by throwing it in too many directions and in an excess of speculative movements; and this sorrow for what is divided gives the face its unity, its final recollection in the boundless depth of remorse.

Leopardi

Leopardi is much loved for having rediscovered some of his most veiled, intangible myths: the graceful Moon, the Maiden, the Sparrow, the Broom, the Infinite, on the very wave of popular sentiment. They almost touch on the realm of fairy tales. School was his vehicle, his tail and his press; once the tedium of compulsory reading ceased, a tenacious residue was illuminated, and the myth was awakened as if by anamnesis.

Leopardi is a wet bandage, a damp screen between the inhumanity that rises in our sky and the melancholic flesh that remains and will die human.

Thirty-nine years of abstinence from women, with a burning and corrosive desire, are a tremendous test. The Canti are best understood by those who see them as the formidable fruit of an unsustainable celibacy, of an almost homicidal absence of the other. The landscape of the Marca, a library, maternal Nothingness, Sexual Abstinence: this is the biological compound of the Canti.

He remained locked up, incubating his fire, with great flights of a Platonic Phaedrus outside the window, struck down by his own paralyzing superiority and delicacy.

To Giacomo, hungry for love, I applied that Lutheran compassion that I like so much: “We are all beggars” (Wir sind Bettler, das ist wahr), and it seemed fair to me, but there is something else behind this tragic shame. The miserable hungry man here is one of the greatest, most noble souls ever to have walked the earth: his hunger is ambiguous. Deep down, Giacomo prefers to keep it alive and biting, rather than humanly satisfying it… The confessions of love to himself are as significant as those in the letters, in the Canti, in the Memoirs of First Love, which throb for the omnipresent erotic phantom woman, now illuminated, now cast into shadow by the oscillating lamp of Great Desire-Sovereign Fear. The tercet “Solo mi corazón pláceme” (Only my heart pleases me) from Primo Amore is extremely important and illuminating, and in the letter to Giordani dated January 16, 1818, the proud impetus “I can well glorify myself before myself, having everything in me” can also be read, in an imaginary erotic transcription, as a glacial rejection of the other, of loving reciprocity, of all sexual exchange.

Leopardi pays with infinite physical pain for the incredibly rapid conquest of his lucidity, in a surprisingly complicated transformation, exciting to follow on paper, of ascetic erudition and effort to live in great lamps of the future. Never relieved of the mournful yoke that bends his poor back, which is like a sign of his angelic heritage, the pain of having taken part in the realm of truth (which is not the arid truth of pure skeptical reason) will reach the limit of the wall that only the mystic can break and jump over, that is, as far as imagination and philosophy can go. But who knows if a crack opened up for him…

Lucretius

The legend that makes Lucretius delirious because of an aphrodisiac is profound: during an intervallum insaniae, the victim of love explodes in a stupendous fury of elucidating the evil that has overwhelmed him.

The entire Lucretian canticle is the desert and chains of a man who lives, all well scrutinized, the evils of the world, pouring uselessly over the wounds of the living, with infinite pity and diligence of a holy monk, the universal Epicurean ointment. In the end, if you raise your eyes to the plague victims of Athens piled up in the squares and on the pyres—a precise vision, of a pestilential solar, of Jeremiah the gravedigger, of the funeral harpist—the light that the remedies full of medicine and goodness promised you has been extinguished: and you wonder how that rigorously condemned poet could promise you a salvation from which he himself, because of his own difficult gift, was excluded.

Excerpts from La fragilità del pensare (BUR Biblioteca Univ. Rizzoli, 2000).

Translation from Italian: Rafael Cienfuegos Lamberti.

Image: Men Reading (1820-1823), by Francisco de Goya.