I

The library is always “dirty.” Its very idea runs counter not only to order but to cleanliness. To live is to live in chaos. Though we may be slaves to its cleaning, the dust is always there, either on the books or on any corner or scrap of wood or metal that has failed to be covered by books. Somewhere in the library there will be a rag or a duster. I have one of those, brightly colored and soft to the touch, though I rarely use it.

We live among tiny excrescences we prefer to know nothing about; we don’t want to see them, we erase them at once. Yet they are there and will remain, we belong to them and they to us. There is a passage in More’s Utopia that tells us gold should be put to use in the making of chamber pots, and some contemporary artist has taken him at his word, producing a golden toilet for an exhibition. The contrast between gold and urine—note how near the words sit to each other—does not lie far from that other pairing of dust and library, though we seldom think of one without the other.

Our relationship to library dust is perhaps our only truly conscious tolerance of the unclean in our lives, our one real coexistence with the transgression of that purifying, hygienic order to which we seem destined by the generalized panic toward illness, especially during Covid-19.

Society kept us under watch; it wanted us healthy by force, hands coated in gel, aseptic bodies commanded to keep six feet apart and to walk along arrows laid out on supermarket floors. They wanted us to respond to the automatisms of a so-called “new normal,” which was nothing but the negation of our original chaos. All of it now sounds like a distant noise, and yet we lived through it.

II

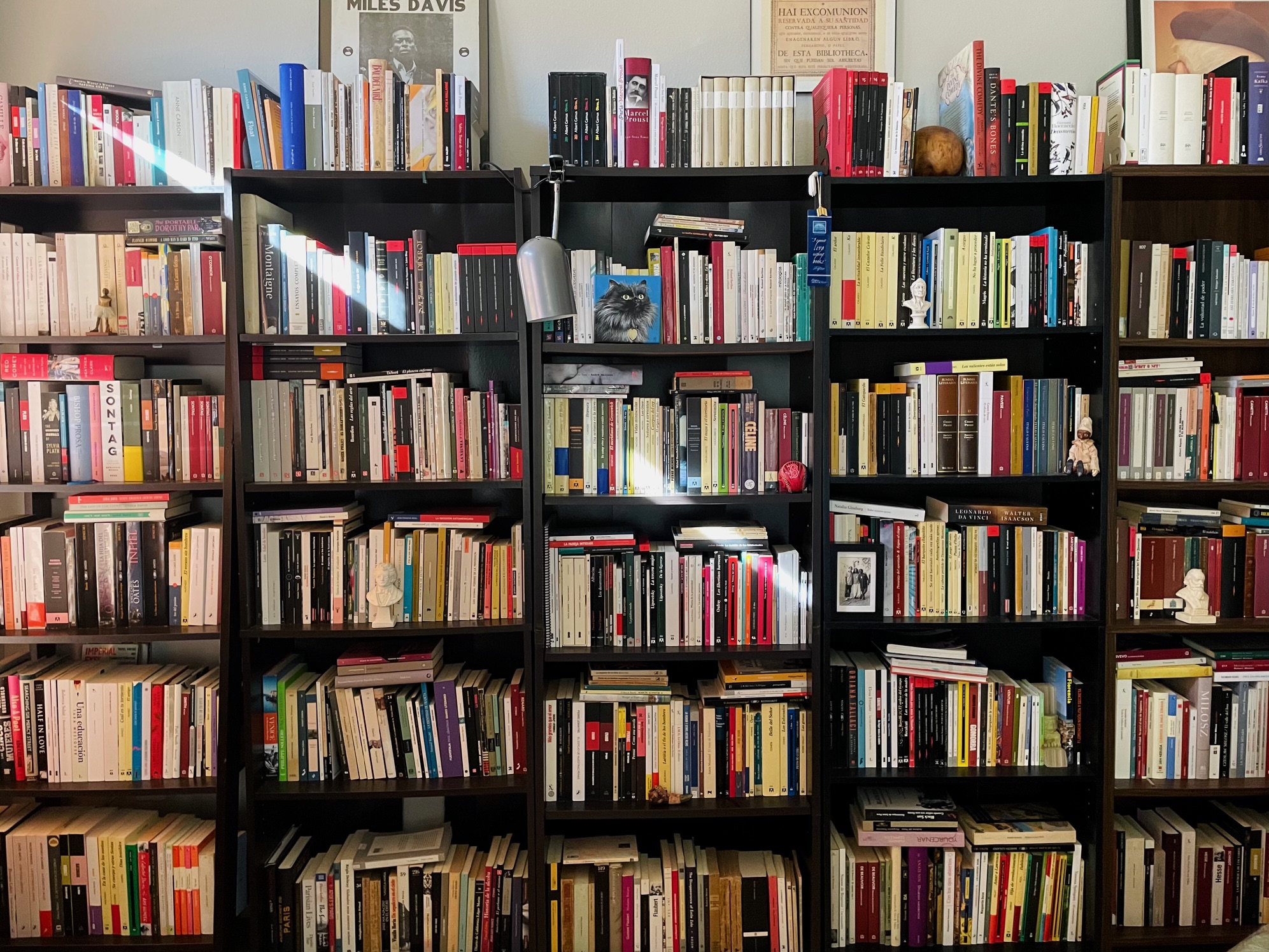

At times I’ve thought that certain corners of my library serve as my alibi to behave as something I am not: an uncritical reader. My shelves hold books by authors I no longer read because they no longer interest me, or never did. And yet their books remain, flickering like the will-o’-the-wisp above forgotten bones. They are mostly Cuban and Latin American writers—no Benedetti, but some Galeano peeks out, shame on me—whom I will scarcely pause over again.

Why keep them then? I suppose because of my chronic incapacity to get rid of anything. Or because someday I may need them to check a fact, a line, an opening or a final page. These are books that (badly) accompanied a segment of my life (here speaks the reader I truly am, never uncritical) and that for some reason deserve to inhabit the walls of the cemetery I’ve built for them and for the rest.

III

In José Martí’s Notebooks I find a reference to William Brewster, one of the Mayflower pilgrims. He reached the coast of North America with 245 books, and he was not, it seems, the one who carried the most. Educated at Cambridge, he had learned Greek and Latin; some say he even traveled with his worktable, now on display at the Plymouth museum. What can those who speak against books know of truth?, Martí asks.

What interests me is not only the founding of a nation with a cargo hold full of books—though that too—but the idea of moves, of traveling with books, especially when they are pieces of one’s own life, chapters of a biography whose meaning belongs to oneself alone. I am always ruminating on such things, because every move I have subjected my family to has been, in essence, a move of books.

I once heard the story that the first university contract Emir Rodríguez Monegal signed to travel to the United States included a clause allowing him to bring his books, the academic authorities imagining, perhaps, a few hundred volumes, when in fact it was an entire shipping container. Is the anecdote apocryphal? Who knows where it could be verified.

For a trip of only a few hours I subject myself to several weeks of packing and then several days of unpacking and arranging. In the last move, from Arkansas to Texas, I did the math: about 125 boxes of books, granted that most were those small wine and liquor boxes we would request from whatever store was nearby.

One of the people who helped me unpack when we arrived was a Cuban from Sagua de Tánamo, for whom the closest approach to a book is roughly the distance between the two poles—North and South—or between that little town in Oriente and this megacity where I live. Whenever I run into him, he’s always telling the same story: I helped unload a moving truck that carried 125 boxes of books. A tale he offers to the astonishment of anyone willing to listen.