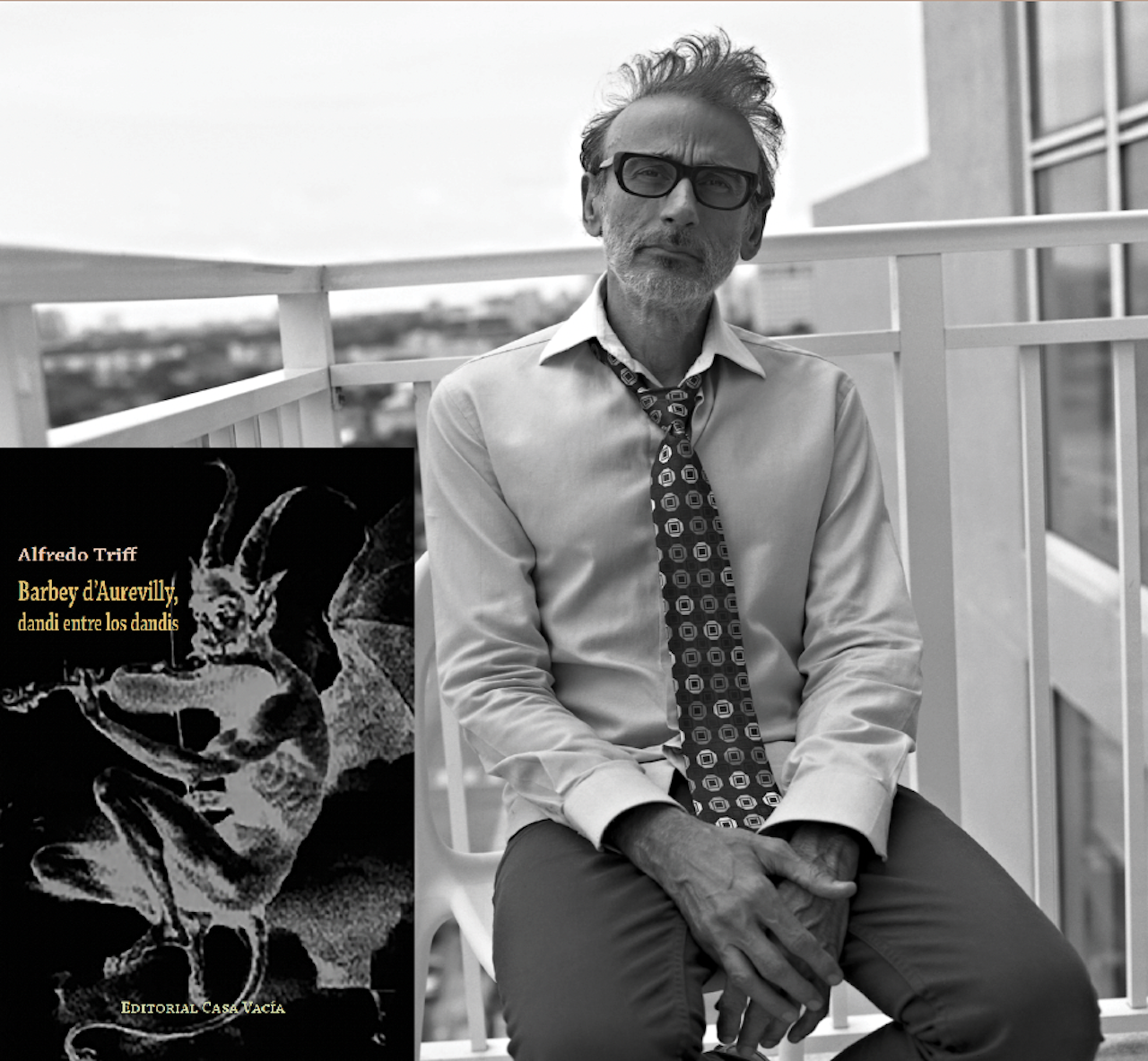

With Barbey d’Aurevilly, dandy among dandies (Casa Vacía, 2024), Alfredo Triff has written a unique essay, halfway between literary criticism and dramaturgy, between exegesis and performance. The book opens with an almost funereal scene, where the adorned body of the old Barbey seems to stage his final myth: to die as he has lived, dressed in the splendor of excess. Triff summons the Norman dandy from a prose turned masquerade… The second half of the volume—a play populated by real dandies discussing art, style, and philosophy in a 19th-century salon—goes beyond the academic framework to delve into the literary. This interview explores the gestures, decisions, and convictions that animate this irreverent work, where each sentence seems dictated not only by erudition but also by an uncommon elegance.

The book opens with an almost forensic description of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s corpse… Why begin with the decay of the body rather than the splendor of the myth?

The dandy’s body is his clothing. That said, the inevitable decay of the body and the splendor of the myth become one.

The prose of Barbey d’Aurevilly, dandi entre los dandis, is not that of a distant academic; it is sententious, ironic, and at times baroque. One could say that Alfredo Triff writes “dandily.” Was it a conscious decision to mimic the style of the subject studied? Or is it that dandyism, in order to be understood, requires prose that is itself a performance?

When talking about masters, I dispense with the self. The second question: it’s futile to fight. When it comes to Barbey, mimicry is unavoidable. I imagine that writing dandily is to elevate prose to the stage—even so, there will always be demodés.

The book is divided into two very different parts: an analytical essay and then a dramatic piece, “Night of Dandies in the Salon of Baroness Almaury de Maistre,” where historical figures converse in a salon. What does fiction or theater allow you that criticism perhaps cannot? Why resurrect these figures in dialogue rather than simply analyzing them?

Criticism is a sterile genre by nature. Just compare literary events in your own backyard: for every ten dedicated to poets, if one is dedicated to criticism (and poorly attended). The fair assessment is: none. For the decadent, it is reality that imitates art. Then, there is nothing more eloquent than presenting an evening of dandies passing time in idle tasteful dissipation—to quote the parodist Max Beerbohm, a dandy from birth.

You draw a clear line between the “dandy,” who lives his myth, and the “dandy writer,” who makes that myth his life and writing.

Is Barbey the perfect fusion point? And in contemporary literature, do you think these figures still exist, or are we left with only nostalgia for that coherence between life and work? There are three in the Olympus, in this order: Barbey, Wilde, and Baudelaire (explaining why would take a while).

They are four excellences to follow: bearing (coba, debonair), theatricality, verbosity (written and spoken), and self-control. The figures? Every era has them, although not all can be discerned right away. To deny this is to ignore the very essence of all tradition, whose permanence, far from opposing change, proceeds through an immutable and imperceptible evolution.

The dialogue section is full of details, from the furniture—the Louis XVI screen, the Pierre Lapautre table—to the jibes between the conversationalists. How did you research to capture not only the facts, but also the voices and atmosphere of that salon? How much freedom did Alfredo Triff allow himself to fill in the gaps in the historical record with his imagination?

I conceived it as an original exercise in interior design. The 1850s in France were an eclectic period between “Nouveau” and Orientalism: luxurious materials, brocades for upholstery, and gilded woodwork. Bronze appears in details and ostentatiously elegant crystal chandeliers. The voices in the salon? Famous dandies and friends in real life. The salon of the Baroness de Meistre is a high-voltage theater, and Barbey acts as the supreme director. The very French plot (including the politics of the time) revolves around the famous Norman, touching on literary themes of the moment. Each dandy assumes his own character. For example: the contrast between the poets Borel and Deschamps. The former is bohemian, performative, and Gothic à la Huysmans; the latter is starched, bucolic, operatic, and Shakespearean. Borel (who called himself lycantrope) was editor of the newspaper Le Satan (considered avant-garde by surrealists such as Breton). Deschamps, alias “Le jeune moraliste,” sought recognition in the most refined circles of the establishment (Goethe admired his poetry). The task is to “decipher” these styles and bring them to life in the salon. Indeed, it is a matter of filling in the gaps, but without ever betraying the spirit of the era.

The book insists that dandyism is a “contempt for the common” and an act of individual sovereignty. In an era like ours, so focused on the collective and political correctness, what place is left for the dandy? Is he a reactionary figure or the most radical form of rebellion?

The dandy is allergic to pedagogy. Persuasion is a futile act. The era? It is a period of digestion. Rebellion consists of waging an internal war and winning it for oneself.

You describe Barbey as an “ardent and unpredictable Catholic” and devote part of the dialogue to his “fixation with the devil,” going so far as to claim that “without the devil there would be no romanticism.” This coexistence of dandyism and Catholicism seems to be one of the great paradoxes of the character. How can the absolute sovereignty of the self, which is the basis of the dandy, be reconciled with the submission demanded by faith? Was Barbey’s Catholicism just another mask, the most sublime and contradictory of all, or is there a secret link between the liturgy of the Church and the aesthetic-personal liturgy of the dandy?

Tricky question. Barbey must have explored the apocatastasis, a heretical theory of the patristic Origen of Alexandria (condemned, after his death, by the Second Council of Constantinople). For both the romantic and the decadent, the fall of Lucifer is the earliest universal event most replete with symbolism. Add to this: between Lucifer (angel of light) and Satan, there is only one sin. It is a fact that Barbey bets on Chateaubriand’s exalted faith in Le Génie du Christianisme. Why this quasi mystical faith of the dandy? It is the best weapon against the tyranny of reason—let us read Pascal’s Pensées, di novo. Why is the defense of the devil a favorite theme of the romantic and the decadent? Lucifer’s stubborn and deluded ego, just before the fall, is far from genuine pride and becomes conceit. And believing oneself to be what one cannot be. Is that faith? No, pure theater! Let us return to the old Origen: could Satan be redeemed from his sins in the Omega of time? If so, the table is set. If not, one can still be Catholic because of that ardent, radical, and lucid faith that accompanies the divine martyr on the Via Dolorosa.