Citario. Derived from the Latin “citāre” (to quote) plus the suffix “-ārium” (repository), similar to “bestiary.” A 21st-century neologism, it emerged among Spanish-speaking scholars at Bookish & Co., with roots in ancient anthologies and florilegia. “Citario” is related to medieval books of commonplaces (such as Erasmus’s) and 19th-century proto-examples, such as “Familiar Quotations.” This “Citario of Paris” celebrates the most literary and bookish city, which is itself writing and an image of the times.

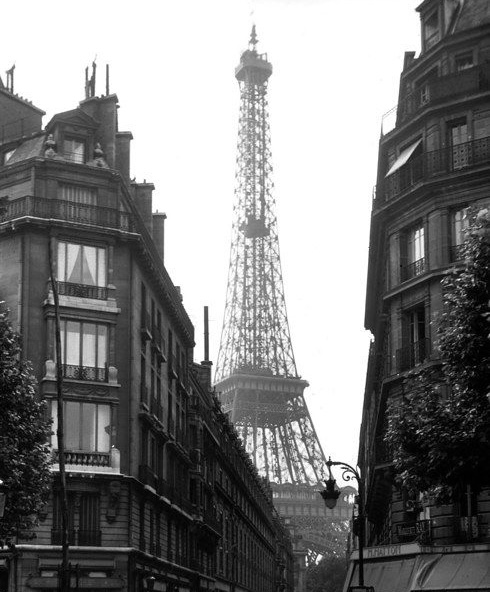

Writers, sculptors, architects, painters, and enthusiasts passionate about the still-intact beauty of Paris, we wish to protest with all our strength, with all our indignation, in the name of poorly appreciated French taste, in the name of threatened French art and history, against the erection, in the heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower. Will the city of Paris continue to be associated with the baroque and mercantile imaginings of a machine builder who has irreparably disgraced and disfigured it? For the Eiffel Tower, which even commercial America would not want, is, without a doubt, the disgrace of Paris. Everyone feels it, everyone says it, everyone is deeply distressed, and we are but a faint echo of the universal opinion, so legitimately alarmed. Finally, when foreigners come to visit our Exhibition, they will exclaim in surprise: What? Is this the horror that the French have come up with to give us an idea of the taste they boast so much about? They will be right to mock us, because the Paris of the sublime Gothics, the Paris of Puget, Germain Pilon, Jean Goujon, Barye, etc., will have become the Paris of Mr. Eiffel.

Le Temps, 14 de febrero de 1887. Extract from the “Protest of the Artists,” signed among others by Ernest Meissonier, Charles Gounod, Charles Garnier, William Bouguereau, Alexandre Dumas (son), François Coppée, Leconte de Lisle, Sully Prudhomme, and Guy de Maupassant.

◾️

In Paris there are endless bookstores; books are seen everywhere. Spring in Paris is the most suitable season for the slow, distracted, meditative walk; the temperature is mild; the sky, as almost always in Paris, shows us its ash-gray hue; the trees spread their foliage in the gentle air. Let us stroll along the bookstalls lining the banks of the Seine. The river glides calmly, steel-colored; through the foliage of the leafy plane trees we glimpse the gray of the sky. We take a book from a stall, leaf through it, and put it back again. Sometimes we buy a volume that invites us to read.

(…)

Everywhere in Paris there are books; the new booksellers do not disdain to sell old books; almost all new bookstores sell old books. And it is rare to find a bookstore in Paris that does not have, at its door, stalls filled with new and old volumes, where the curious passerby can rummage at leisure. You can see poor readers standing with a book in hand, a book just off the press, trying to go on reading, carefully parting the uncut pages. Sipping like bees at a flower—sipping imperfectly—these impoverished readers can form an idea—a fragmentary idea—of the book that has just been published.

Azorín, Books, Booksellers, and Libraries. Chronicles of a Wanderer: Madrid–Paris

◾️

Maupassant often had breakfast at the restaurant in the Tower, but he did not like the Tower: “It is,” he said, “the only place in Paris from which I cannot see it.” Indeed, in Paris one must take endless precautions not to see the Tower; in any season, through the mist, the early light, the clouds, the rain, in full sunlight, wherever one may be, whatever landscape of rooftops, domes, or foliage separates one from it, the Tower is there, so thoroughly incorporated into everyday life that we can no longer invent for it any particular attribute. It simply insists on persisting, like the stone or the river, and is literal like a natural phenomenon, whose meaning we may question endlessly but whose existence we cannot doubt. There is hardly a Parisian gaze that it does not touch at some moment of the day; as I begin to write these lines, it is there before me, framed by my window; and at the very moment when the January night blurs it and seems to wish to make it invisible, to deny its presence, two small lights come on and gently blink, turning at its summit: all through this night it will also be there, linking me, above Paris, to all those friends of mine whom I know are seeing it; together we form with it a moving figure of which it is the fixed center: the Tower is friendly.

Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower. Texts on the Image

◾️

The true purpose of Haussmann’s works was to secure the city against civil war. He wanted to make any future uprising of barricades in Paris impossible. It was with this intention that Louis-Philippe introduced wooden block paving. And yet, the barricades still played a role in the February Revolution. Engels discusses the technique of fighting on the barricades; Haussmann sought to prevent it in two ways. The width of the streets would make their construction impossible, and new streets would establish the shortest route between the barracks and the working-class neighborhoods. Contemporaries would christen the enterprise l’embellissement stratégique — “strategic beautification.”

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” (Illuminations)

◾️

Rimbaud, so young at the time of the Commune barricades, did not resist this illusion. Paris is the “holy city,” he writes, the “chosen city,” blessed by the past, “the head and both breasts thrust toward the Future,” the community that “the storm” (in this case, the revolutionary days) consecrated as “supreme poetry” forever. The identity of the metropolis in its excess of self and of poetry—an excess of spirit over language—found in those verses of “Paris is Repopulated” its most astonishing expression. And yet everything began to change. This poem, or “The Hands of Jeanne-Marie,” which speak of such enthusiasm, are contemporaneous with the crushing of the Commune, which was the last act of mutual recognition, of solidarity under the sign of the future, that the Parisian multitude would ever know—excepting the days of 1944. And when Rimbaud came to live here, he was astonished, disappointed; he did not stay, but fled to the ends of the earth with his bitter disillusionment. “Let the cities light up in the evenings! My day is done; I abandon Europe,” he exclaims in A Season in Hell, while some of the Illuminations—those very ones simply called “Cities”—work an extremely significant transformation on the idea of the urban place.

Yves Bonnefoy, The Century of Baudelaire

◾️

The faubourg Montmartre, where Flaubert situates the Art industriel and Rosanette’s successive residences, is the quintessential neighborhood of successful artists (for example, Feydeau and Gavarni live there—Gavarni would coin in 1841 the term lorette to designate the courtesans who swarm around the Notre-Dame de Lorette area and the Place Saint-Georges). Like Rosanette’s salon, which is in a sense its literary transfiguration, this neighborhood is the place of residence or meeting point for financiers, successful artists, journalists, and also actresses and lorettes. These men and women of the demi-monde who, like the Art industriel, occupy a halfway position between bourgeois and working-class districts, stand opposed both to the bourgeois of the chaussée d’Antin and to the students, modistes (seamstresses), and failed artists—whom Gavarni harshly ridicules in his caricatures—of the Latin Quarter.

Arnoux, who in his prosperous days belongs by his home (rue de Choiseul) and his workplace (boulevard Montmartre) to both the world of money and the world of art, is first expelled toward the faubourg Montmartre (rue Paradis), before being relegated to the outermost margin of the rue de Fleurus. Rosanette too moves within the space reserved for the lorettes, and her decline is marked by a progressive shift eastward, that is, toward the borders of the working-class neighborhoods: rue de Laval; then rue Grange-Batelière; and finally boulevard Poissonnière.

Pierre Bourdieu, “The Paris of Sentimental Education” (The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field)

◾️

Then one could say that Paris—let’s see what Paris is—is a gigantic reference work, a city one consults like an encyclopedia; you open a page and it gives you a whole range of information, richer than that of any other city. Take the shops, which constitute the most open, the most communicative discourse a city expresses. All of us read a city, a street, a stretch of sidewalk by following the line of its shops. There are shops that are chapters of a treatise, shops that are entries in an encyclopedia, shops that are pages of a newspaper. In Paris there are cheese shops where hundreds of different cheeses are displayed, each labeled with its name: cheeses wrapped in ash, cheeses with walnuts—a kind of museum, a Louvre of cheeses. These are aspects of a civilization that has allowed for the survival of differentiated forms on a scale large enough to make their production economically viable, while still maintaining their raison d’être by presupposing a possibility of choice, a system of which they form part, a language of cheeses. But above all, it is also the triumph of the spirit of classification, of nomenclature. So if tomorrow I set out to write about cheeses, I can go out and consult Paris as a great encyclopedia of cheeses. Or I could consult certain grocers in which one can still recognize what exoticism was in the last century—a commercial exoticism of early colonialism, let’s say, a spirit of the universal exposition.

Italo Calvino, Hermit in Paris: Autobiographical Pages

◾️

Paris, singular country, where it takes 30 sols to dine, 4 francs to take the air, 100 louis to have the superfluous within the necessary, and 400 louis to have nothing but the necessary within the superfluous. Paris, city of amusements, of pleasures, etc., where four-fifths of the inhabitants die of sadness.

Nicolas de Chamfort, Maxims and Thoughts, Characters and Anecdotes

◾️

Paris. People walk quickly, pushed along by the cold. But the city does not falter. Each time you return, you think it will no longer be the same, and it’s true that some things change, disappear, or suddenly appear—but you are still in Paris. There are more Chinese, Thai, or Lebanese restaurants in the neighborhood. The cafés change their menus (they’ve Italianized them, with culinary touches of an Italy that exists everywhere in the world except in Italy; though, truth be told, it’s beginning to appear in Italy as well). Fusion dishes abound, with more or less exotic salads, and yet it’s becoming difficult to find a good casse-croûte of rillettes. Still, there are enough traces at street level for the city to remain itself—and then, of course, there is its immutable architecture, its calling to be a showcase city.

In Place Maubert, the street market continues, as do the delicatessen, the cheese shop, the wine store, the bakery: you step into those shops and you’re in the Paris you never want to see disappear—the Paris that gathers the best of the French countryside. One can live in a small hotel like the one I’m staying in and have no need to walk more than a few hundred meters to find the best of what one desires in a civilized life. The city—at least in the center—is itself in every corner. Every corner of central Paris is all of Paris. You can spend a good part of the day shielding yourself from the cold in your hotel room, but then you go out, take a walk around the neighborhood you’ve been allotted on this trip, and it’s not that you’re taking a walk through Paris—it’s that you have the whole of Paris to yourself.

This time, Place Maubert. Within just a few meters: the cafés, the newsstand where I buy the Spanish newspaper, the street market with its well-stocked vegetable stalls, and the shops that open their doors beside it—the charcuterie, with its gelées; the cheese shop, with its strong perfume and its dozens of cheeses from every corner of the country; the bakery, the smell of bread crackling in the air—pure Pavlovian dog reaction, oh those baguettes, those croissants; a bit further on, the chocolate shops, the bookstores along Boulevard Saint Germain.

I spent a few months in Paris when I was nineteen, a penniless student. I hated the distance the city imposed on me, that feeling of helplessness, of self-absorption, which I now, however, experience as freedom (surely thanks to having a bit more money). I put on my headphones to listen to music and walk several kilometers every day, eating a croissant as I go (you have to take advantage—later I’ll spend months and months in Beniarbeig without tasting a crisp, ethereal croissant again; or a baguette stuffed with some sausage or pâté I like). Flâneur. To come back to the hotel exhausted and take out the oeufs en gelée or the tête de veau you’ve kept almost clandestinely in the little room fridge; to listen to the baguette crack as you break it with your hands and uncork a small bottle of Burgundy—surely there’s no one happier in the world at that moment than I am. Then I lie on the bed and open the book I’ve just bought, the title of which I’d written down months ago on a scrap of paper.

Yes, a yokel in Paris. What can you do. It’s been nearly forty years that this city has seduced me, a city that has managed to elevate the rustic into urban refinement: breads, sausages that smell like a pig’s backside and taste like filth, wines; a country where people spend their days filling page after page of rhetoric to explain that the rumsteak or tournedos appearing on the plate of a Michelin-starred restaurant comes from a farm, has passed through a butcher’s shop, and is to be appreciated if it retains a thread of blood that stains the plate when the knife cuts into the meat. In Paris, people like to recall that the most elegant furniture is made by a cabinetmaker; that paintings are framed by artisans (their workshops still exist in the courtyards of elegant houses as well as poor ones—poke your head into a doorway and you’ll see the cabinetmaker at work); that the pig or the sheep was raised by a farmer from Auvergne.

That relationship—the recognition, even veneration, of the thread connecting high and low—is something I greatly admire in the French character (in Castile, a country, hélas, with almost no bourgeoisie, it has not been so: until recently, the product hid its origin; the producer was deprived of value and respect). Among those continuities of Frenchness, one must include the passion that haute cuisine (Parisian, but especially Lyonnaise) feels for offal—the taste for strong aromas, those cheeses whose smell and flavor recall the scents of stables, the hides of mammals, even their excrement. Those andouillettes, sausages containing intestine wrapped in intestine, which are appreciated all the more the more intensely animal their flavor… You eat them as if you were being invited to a colonoscopy.

Rafael Chirbes, Diarios. A ratos perdidos 3 y 4

◾️

When I arrived in Paris, I immediately understood my interest in idle people. I myself am an example of the unproductive: I have never worked, never had a profession, except once, for an entire year in Romania, when I taught philosophy in Brașov. It was unbearable. And at the same time, that was the very reason that brought me to Paris. In one’s own country, one must do something—but not necessarily when one lives abroad. I have had the good fortune to live more than forty years as an idler and, how shall I put it, without a State. I believe what is interesting about living in Paris is that one can—one must—live here as a radical foreigner, in such a way that one does not belong to a nation but only to a city. To some extent I feel Parisian, but not French—especially not French. (…)

There are two books that for me represent, express Paris. First, that book by Rilke, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, and then Henry Miller’s first book, Tropic of Cancer, which shows another Paris—not Rilke’s Paris, but even its opposite, the Paris of brothels, of prostitutes and pimps, the Paris of mud. And that is the Paris I knew: (…) the Paris of lonely men and prostitutes.

In fact, I had already experienced it in Romania: the life of the brothel was very intense in the Balkans; just as it was in Paris, at least before the war (…) when I arrived here I used to have long conversations with many women. At the beginning of the war I lived in a hotel, not far from Boulevard Saint-Michel, and there I befriended a prostitute, an older lady with gray hair. We became very good friends—that is to say, she was too old for me. But she was an incredible actress, with an immense talent for tragedy. Almost every night I would run into her around two or three in the morning, for I always returned late to the hotel. It was at the beginning of the war, in 1940—or no, it was before, since during the war no one could go out after midnight. We would walk together, and she would tell me about her life, her whole life, and the way she spoke of it all, the words she used, fascinated me. (…) The experiences I have had in my life with that kind of people have taught me more than my relationships with intellectuals.

Emil Cioran, “Je ne suis pas un nihiliste: le rien est encore un programme” (I Am Not a Nihilist: Nothingness Is Still a Program, interview published in Magazine Littéraire, Paris, no. 373, February 1999. From Gerardo Fernández Fe’s blog)

◾️

In twenty years, the elegant and distinguished city would thus have become a democratic one; the orderly, aristocratic Paris of the Restoration and the July Monarchy would have taken on the aspect of a maelstrom or a Babel—two images that evoke the chaos of mass civilization. Baudelaire presents this rupture as a form of decadence: not as a more rational organization of urban space—cut through by wide, brightly lit avenues that eliminate the sordid medieval labyrinths—but as a disintegration from which the city of Paris would have emerged utterly disoriented.

In just a few years, the epicenter of Parisian life shifted from the Palais-Royal—depicted since the seventeenth century as a suspect tangle of gambling houses and prostitution, as in Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s famous Tableau de Paris (Picture of Paris)—to the boulevards. But Baudelaire sees that mutation in the city’s cultural geography differently: for him, literary life withered away to the benefit of other, more egalitarian pastimes.

Antoine Compagnon, A Summer with Baudelaire

◾️

This close relationship among all the elements that make up Paris—the tragic and the frivolous, the working and the dissipated—has ended by creating a city of pure nerves, spiritual champagne, as the English say.

For three days I have felt myself living outside myself, as if my spirit had ceased to belong to me, filled instead with the vibration, the vision, and the luminosity—to put it plainly, for Paris is all light—of a city. This had never happened to me before, and I have resolved to visit Paris more often.

But I will never stay in Paris for more than three days. It is a bath of light, of electricity, and of champagne. It is very good, from time to time, for any man who lives a solitary life of work. It is good to shake off the drowsiness of everyday living and, in that shaking, to find the energy necessary to go on enduring it—but one must go on enduring it. And the man who comes to feel Paris within his soul for several months—will he then have the strength required to gather himself again into his work?

Ramiro de Maeztu, “Three Days in Paris” (Autobiography, Madrid, 1962)

◾️

At six in the morning the mist was rising from the ground and a drizzle began to soak into the bones. The cold was such that by the second corner my jaw was locking up, and that was when the hardest part began: crossing the Bois de Boulogne to reach the public pool at the University of Paris-Dauphine, where the showers were. In fact, one of the first times I crossed the woods I witnessed something disturbing. A homeless man had frozen to death during the night, and as I passed by I found a group of rescuers lifting his body. But there was a problem: when the man had fallen to the ground (at the moment of death), his left hand had sunk into a puddle of water, and when the temperature dropped, it froze. I remember the sound of a stiletto breaking the ice around the hand. The hand trapped in the ice that kept them from lifting him. I walked away thinking that the hand, because of the freezing, might still be alive—and in truth, I dreamed of it several times afterward.

Santiago Gamboa, The Ulysses Syndrome

◾️

The secret of great cities lies in offering to their wanderers walks whose charm is often inexplicable; and however much I am told that my satisfaction comes from the beauty of the houses, the depth of the courtyards, and the age of the stones, there is something more to it—something words can only allude to: that certain lightness of spirit produced by the sight of a tree beside a rooftop or, on a sunny street, the sudden freshness of a vaulted shadow beneath the disdainful crossbeams of an old mansion.

Thus, any pretext serves me well for roaming through that marvelous provincial city that stretches from the gates of the Luxembourg Gardens to the Pont des Saints-Pères, dominated by the bell tower of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the twin towers of Saint-Sulpice; and I could say of it what old Samuel Johnson more or less said of London—that if one tires of its streets, it means one is tired of life itself…

Julien Green, Paris

◾️

The important thing is not that the edict of 1539 [on urban sanitation] took effect and that Paris, city of shit, emerged from its mire. In fact, two and a half centuries later, Louis-Sébastien Mercier would paint a picture of the capital as apocalyptic as the one before, and in it, garbage would continue to occupy its usual place. And, although Zola came after the laws of hygiene had been established as integral parts of positive science, the image he would give us of Paris would be no less cloacal, muddy, and dark than it was in the Middle Ages, an era in which, in retrospect, the city was described as repugnant by the historians of the time.

Dominique Laporte, History of Shit

◾️

Everyone has an idea of what Paris is or could be, whether they have been there or not. This happens with two or three places in the world, with Venice or with Rome, for example, but it doesn’t happen with other no less famous cities, which always add or subtract something from the idea one had of them, like London, which ends up being something other than what we had thought, for better or for worse. Not Paris. Paris, like Venice or Rome, can only be as it is, and one is not surprised that it is so, perhaps because when one arrives, one does nothing but confirm what Balzac or Zola or Proust told them.

It is a mystery why this happens. Perhaps it happens because Paris is a state of the soul, or rather, the final degree in which sadness becomes tolerable. One degree more, and we would die. I believe that in no city can one feel as lonely or as miserable as in Paris, and also the complete opposite. The solitude in Paris, the wide boulevards, the river, the refined shops, the opulence of the perfume that Parisian women leave behind them, the happiness everywhere, in short, make one feel small, but the awareness of one’s smallness ends up fluffing up one’s soul and making it great. Anyone who has accompanied Rilke’s Malte on his itineraries will know what we are talking about, as will all those who, despite feeling unhappy, have sought refuge in Paris: from the exiled and attractive Wilde or the insatiable miniaturist Walter Benjamin to the last of the last exiles counting their final pennies on the foul-smelling bedspread of a miserable garret.

Andrés Trapiello, “We’ll Always Have Paris” (Sea Without Shores)

◾️

But in those youthful days in Paris, I believed that joy was foolish and vulgar, and with a notable imposture, I pretended to read Lautréamont and never stopped bothering my friends by suggesting at all hours that the world was sad and that I would soon commit suicide, as I only thought about being dead. Until one day I ran into Severo Sarduy at La Closerie des Lilas and he asked me what I was planning to do on Saturday night. ‘Kill myself,’ I replied. ‘Then let’s get together on Friday,’ Sarduy said. (Years later I heard Woody Allen say the same thing and was stunned; Sarduy had anticipated him.)

Enrique Vila-Matas, Never Any End to Paris

◾️

The king ordered the construction of the Louvre, whose completion was so desired, he built a city in Versailles near that castle, which cost so many millions, he built the Trianon and Marly, he had many other buildings embellished and he also ordered the construction of the Observatory, which began in 1666, at the time he founded the Academy of Sciences. But the most glorious monument for its usefulness, its grandeur and the difficulties that had to be overcome, was the Languedoc canal, which joins the two seas and flows into the port of Cette, built to receive its waters. All that work began in 1664 and continued without interruption until 1681. The founding of the Invalides and the chapel of that building, the most beautiful in Paris; the establishment of Saint-Cyr, the last of the works built by the monarch, would be enough to bless his memory. Four thousand soldiers and a large number of officers, who find consolation in their old age and help for their wounds and needs in one of those great asylums, two hundred and fifty young women who receive a worthy education in the other, are so many more voices that acclaim Louis XIV. The establishment of Saint-Cyr will be surpassed by the one that Louis XV has just founded to educate five hundred gentlemen; but instead of making Saint-Cyr forgotten, it makes it remembered; what has been perfected is the art of doing good.

Voltaire, The Age of Louis XIV

◾️

Anyone who has ever crossed the Czech Republic, Poland, or East Germany will have seen very sad and gray towns and cities. Naturally, Paris is nothing like them; it is very different. But—and this is what Bogdan Konopka tells us with the calm voice of his photographs—if you look closely at some Parisian neighborhoods, alleys, and courtyards, you might see in them, as if in an ancient mosaic, a small fragment of Mikolów or Plzen, a piece of Myslenice or East Berlin. And this will be no crime of

lèse-majesté; there is no intention of attacking Paris here. Rather, it is an attempt to find what the great capitals and the modest towns on the European periphery have in common, to build bridges between the humble and everyday and the imperial and splendid.

Adam Zagajewski, A Defense of Ardor